IDPs of Lower Assam: Twenty-one years of displacement and suffering

“The millions of displaced people in India are nothing but refugees of an unacknowledged war…..” – Arundhati Roy

On a sunny Sunday in late August, our vehicle parked in front of Hapachara Lower Primary School adjacent to National Highway 31, a four hour journey from Guwahati, the gateway to North-eastern states of India. The smooth road, beautiful hills and never-ending greenery almost made us forget that we were in search of a black spot of human history, the internally displaced persons camp located in Hapachara village under Bongaigaon district of Assam. We approached a scrap vendor taking shelter under a huge tree and asked for directions.

Forty five year old Romej Uddin not only showed us the way to the camp, but also informed us that he himself is a  camp inmate. The left bylane from the National Highway took us to the village. As the street narrowed, we suddenly came upon a congested human settlement across just over an acre of land. An elderly person sitting in a medicine shop warned us that the actual camp is just ahead. We crossed a small plot of agricultural land and found another settlement, more congested, filthier and more inhuman. A few people were sitting under a tin roofed open house without any walls, door or window, and some women were drying boiled rice grain nearby. As we joined the group in the open house, within a few minutes the house filled up. Everyone had a grimy story to tell, everyone had a reason to lament, and yet, everyone also held a dim ray of hope for a brighter day to end their two decades long journey of suffering and betrayal.

camp inmate. The left bylane from the National Highway took us to the village. As the street narrowed, we suddenly came upon a congested human settlement across just over an acre of land. An elderly person sitting in a medicine shop warned us that the actual camp is just ahead. We crossed a small plot of agricultural land and found another settlement, more congested, filthier and more inhuman. A few people were sitting under a tin roofed open house without any walls, door or window, and some women were drying boiled rice grain nearby. As we joined the group in the open house, within a few minutes the house filled up. Everyone had a grimy story to tell, everyone had a reason to lament, and yet, everyone also held a dim ray of hope for a brighter day to end their two decades long journey of suffering and betrayal.

There are 1118 families living in the Hapachara IDP camp set up on a piece of private land measuring 10 bighas  (nearly 1 and half hector) owned by Rustam Ali in 2000 against an annual rent of Rs. 7000. On October 7, 1993, the Bodo militants started targeted violence against the Muslim minority (Muslims constitute some 30 percent of the state population) of Sidli subdivision, Kokrajhar district, Assam. The violence spread to other Muslim dominated villages in Bijni subdivision, Bongaigoan district (presently under Chirang district after the district reshuffle under the BTC Accord) and the arson continued till October 11. Officially 3658 families or about 18000 people were affected by the violence (Goswami 2008). As many as 72 people lost their lives in the massacre.

(nearly 1 and half hector) owned by Rustam Ali in 2000 against an annual rent of Rs. 7000. On October 7, 1993, the Bodo militants started targeted violence against the Muslim minority (Muslims constitute some 30 percent of the state population) of Sidli subdivision, Kokrajhar district, Assam. The violence spread to other Muslim dominated villages in Bijni subdivision, Bongaigoan district (presently under Chirang district after the district reshuffle under the BTC Accord) and the arson continued till October 11. Officially 3658 families or about 18000 people were affected by the violence (Goswami 2008). As many as 72 people lost their lives in the massacre.  Officially, compensation for death was provided to only 10 or so families (Hassan 2014). The inmates of this camp are from Sidli subdivision of Kokrajhar district. After the violence, they were taking shelter in a government manned relief camp at Patabari under Sidli police station for two years. Though paramilitary forces were deployed to provide security to camp inmates from the attack of Bodo militants, yet within a couple of months two persons, Harej Ali and Gunjar Ali were killed by the militants just outside the camp. To avoid further attacks the camp was shifted to Anandabazar, on the other side of the Kanamakra river. Even there the insecurity continued, with one Baser Ali killed near the river by smashing his head by stone. It was almost impossible for the inmates to go outside the camp. They were strictly instructed by the security personnel not to go outside the camp without permission and getting permission was not an easy task. The eyewitnesses describe the horrifying physical and mental consequences of daring to break the order. They were literally confined in the camp. One day, the security personnel suddenly disappeared from the camp, and the government food and other essential relief supplies were stopped. The inmates then had no option but to leave the camp.

Officially, compensation for death was provided to only 10 or so families (Hassan 2014). The inmates of this camp are from Sidli subdivision of Kokrajhar district. After the violence, they were taking shelter in a government manned relief camp at Patabari under Sidli police station for two years. Though paramilitary forces were deployed to provide security to camp inmates from the attack of Bodo militants, yet within a couple of months two persons, Harej Ali and Gunjar Ali were killed by the militants just outside the camp. To avoid further attacks the camp was shifted to Anandabazar, on the other side of the Kanamakra river. Even there the insecurity continued, with one Baser Ali killed near the river by smashing his head by stone. It was almost impossible for the inmates to go outside the camp. They were strictly instructed by the security personnel not to go outside the camp without permission and getting permission was not an easy task. The eyewitnesses describe the horrifying physical and mental consequences of daring to break the order. They were literally confined in the camp. One day, the security personnel suddenly disappeared from the camp, and the government food and other essential relief supplies were stopped. The inmates then had no option but to leave the camp.

The majority of the Muslims of present day BTAD (Bodoland Territorial Area Districts) are of Bengal origin, while a small number are aboriginal converts to Islam from Koch Rajbongshi. After Assam, a scarcely populated and natural resource rich province, was annexed by the British in 1826 through the treaty of Yandaboo, the British administration encouraged migration of agricultural workers from densely populated Bengal. The advent of the Indian Railway and migration friendly policy helped the administration to bring large numbers of Muslim agricultural workers from Bengal. The colonial administration introduced family tickets from Bengal to Assam, recruited colonization officers in Nagaon, Barpeta and Darrang to look after the issues of migrants. From the early 1930s however, the aboriginal Assamese communities started opposing the migration of Bengalis. After India’s independence and partition, another flow of migration started however, of Hindus from newly formed Pakistan (Guha 2011).

After three decades of independence, an unprecedented movement against migrants took place in Assam. Initially, the ‘Assam Movement’ focused on aboriginal unification against all other Indian ‘bohiragot’ or outsiders. According to some political analysts however, the intrusion of right wing ideologists like RSS into the movement leadership caused it to become a movement against the Bengali origin Muslims (Citizens’ Rights Preservation Committee (CRPC), Assam 2011). The peaceful democratic movement eventually became violent, and within a few hours on February 18, 1983 more than 3000 Muslims of Bengali origin were killed in Nellie, Nogaon district (present day Morigaon). Similar attacks happened in Chaolkhuwa Sapori, Gohpur, Mukalmuwa (Goswami 2013). After six long years, the movement under the leadership of the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU) came to an end through the “Assam Accord” in 1985.

Various Assamese tribes participating in the Assam Movement realized that the ‘Assam Accord’ was not going to serve their aspirations. Decision making power within the AASU and their subsequent political party called the Asom Gana Parishad had been hijacked by upper caste Hindus. The Bodo leadership which was earlier demanding for a union territory for plains tribes called ‘Udayachal’, narrowed their demands to an exclusive ‘Bodoland’, a full-fledged state. Since the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Bodo underground group targeted mainstream Assamese people in present day BTAD area. In 1993 for the first time, Muslims were targeted on a large scale. The inmates of Hapachara camp were among the victims of this violence.

Subsequent to the violence and large scale displacement, the Bodo Accord of 1993 was signed between the government and the All Bodo Students’ Union (ABSU)/ Bodo Peoples’ Action Committee. The Accord formed the Bodoland Autonomous Council, comprising a contiguous geographical area between the river Sankosh and Mazbat/river Pansoi. The Accord entitled villages having more than 50 percent Bodo population to be included in the council. It was not an easy task for the Bodo leadership to find adequate villages having more than 50 percent Bodo population without eliminating other tribes from such villages. For this reason, targeted violence against Non-Bodos intensified after the formation of the council, seen as a process of ethnic cleansing (Rajagopalan 2008).  In 1994, a relief camp of Muslim IDPs in Bashbari, Barpeta district (now in Baksa) was attacked by Bodo militants. Nearly a hundred inmates were massacred in the government manned relief camp at Bashbari High School. These growing incidents of violence, insecurity and complete breakdown of livelihood options mounted pressure on the inmates of Anandabazar relief camp. They finally left the camp without knowing where they were heading to, merely desperate to get away from the reach of the Bodo extremists. They found Rustam Ali, who agreed to give his 10 bighas of agricultural land at the present location to set up a temporary camp against an annual payment of Rs. 7000. In the last 14 years the rent has increased manifold; today they are paying Rs. 48000 per annum.

In 1994, a relief camp of Muslim IDPs in Bashbari, Barpeta district (now in Baksa) was attacked by Bodo militants. Nearly a hundred inmates were massacred in the government manned relief camp at Bashbari High School. These growing incidents of violence, insecurity and complete breakdown of livelihood options mounted pressure on the inmates of Anandabazar relief camp. They finally left the camp without knowing where they were heading to, merely desperate to get away from the reach of the Bodo extremists. They found Rustam Ali, who agreed to give his 10 bighas of agricultural land at the present location to set up a temporary camp against an annual payment of Rs. 7000. In the last 14 years the rent has increased manifold; today they are paying Rs. 48000 per annum.

Though they escaped from the fear of persecution and execution, their plight continued to follow them in the form of starvation, malnutrition, disease, lack of education and livelihood. Seventy-year-old Abdul Jalil once had 26 bighas of agricultural land, more than 15 cows and his own house to live in. In the camp, he has nothing beyond a sense of security. The government has demonstrated only indifference towards these uprooted people. The inmates of various camps united and continued various protest demonstrations and demanded their safe return to their villages. Over a decade later, they are still waiting for some response. Many of the inmates migrated to various cities in search of livelihoods. They went as far as New Delhi to work as rag pickers, construction workers, domestic help and so on. Abdul Jalil’s two sons are working as agricultural labourers in Nagaon districts of upper Assam.

In 2003, the government gave more power to the Bodo militia through a tripartite agreement signed by the State/Provincial Government of Assam, Central/Federal Government of India and the surrendered Bodo Liberation Tigers BLT. This agreement created the Bodoland Territorial Council (BTC) with a demarcated geographical area and constitutional validity under the sixth schedule of the Indian Constitution. Impunity was given to the perpetrators of violence and not a single legal case was pursued against the multitude deaths and displacement. As many as 28 state government departments were transferred to the councils, while the central government was directed to provide a 100 crores annual fund for infrastructural development. The accord made a provision of a 46-member council, with 30 reserved seats for Scheduled Tribes, five seats for non-Tribals, five seats open and six seats to be nominated by the Governor of Assam. The demographic profile of the demarcated area constitutes 28 percent scheduled tribes, while the remaining 72 percent is made up of non-tribals including Muslims, Adivasis, Koch Rajbongshis, Assamese and Bengali Hindus. In other words, 75 percent of seats are reserved for 28 percent of the citizens, while 25 percent of seats are reserved for 72 percent of the citizens. This was not the only attempt to forbid the political participation of the area’s social majority within the council. The accord dismantled the Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) within the council area, to be replaced by the Village Council Development Committee, selected by the BTC. The PRIs were given the authority and responsibility to oversee development under the 73rd amendment of the Indian Constitution, as well as to ensure the participation of all sections of society, including marginalized groups like scheduled castes, scheduled tribes and women. In 1996, the government extended PRIs in scheduled areas as well, under the Panchayat (Extension to the Schedule Area) Act. Paradoxically, the BTC replaced the PRIs with the Village Council Development Committee, which literally keeps non- Bodos away from grassroot developmental decision making.

The accord showed a ray of hope however, for those displaced by the ethnic violence, especially the inmates of Hapachara camp. Section 13 of the accord talks about a Special Rehabilitation Programme (SRF), under which the BTC was to provide suitable land for the rehabilitation of the displaced persons. This provision not only gave hope to the displaced Muslims, but also the lakhs of displaced Adivasis who were uprooted by the Bodo militants through a series of violent attacks in 1996 and 1998. Over a decade later, not a single family has yet been rehabilitated under the programme.

The camp inmates of Hapachara, Bordup, Garogaon, Salabila, Bangalduba continued their struggle in the form of democratic protest, sit-ins, hunger strikes. In 2004, after more than a decade of their displacement, the Assam Minister of Rehabilitation visited inmates in their camps and agreed to provide 10 days of ration per month. Government officials showed up one day to survey the camps without prior notice to the inmates. The inmates who had gone to work in nearby towns or villages and those who had migrated to other places were deliberately not included in the list of beneficiaries. In Hapachara camp more than 500 families were excluded and deprived from minimum government support. A total of 1685 families in all camps who were displaced in 1993 were deprived from getting the monthly 10 day ration.

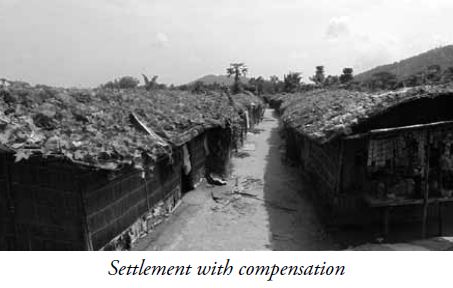

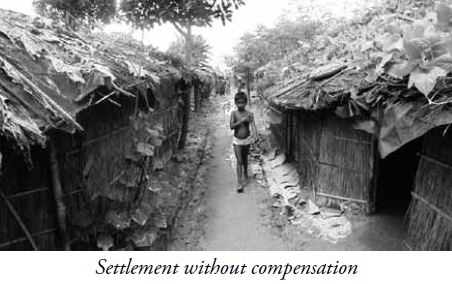

The inmates continued their struggle jointly, demonstrating in front of the state secretariat in Dispur. Finally in  2010, the Assam Government agreed to compensate the IDPs with Rs. 50,000. The government refused to resurvey the camp however, and instead stipulated that only the displaced families who had received a) 10 days ration per month and b) Rs. 10,000 compensation in 1995 will be eligible for the rehabilitation package of Rs. 50,000. In this process, 95 families from Hapachara camp who had received 10 days ration but not the Rs. 10,000 were dropped from the list. As a result only 557 families received Rs. 50,000. Amongst all the camps, the total number of deprived families is more than 1600. The government further stipulated that after receiving the Rs. 50,000, the family will have to leave the camp forever. Is

2010, the Assam Government agreed to compensate the IDPs with Rs. 50,000. The government refused to resurvey the camp however, and instead stipulated that only the displaced families who had received a) 10 days ration per month and b) Rs. 10,000 compensation in 1995 will be eligible for the rehabilitation package of Rs. 50,000. In this process, 95 families from Hapachara camp who had received 10 days ration but not the Rs. 10,000 were dropped from the list. As a result only 557 families received Rs. 50,000. Amongst all the camps, the total number of deprived families is more than 1600. The government further stipulated that after receiving the Rs. 50,000, the family will have to leave the camp forever. Is  Rs. 50,000 enough to rehabilitate a family which lost everything in the course of forced displacement? Today, there are two settlements in Hapachara: one is of those IDPs who have received the Rs. 50,000 and the other is of those who are still fighting for the package. There is little difference between the two camps.

Rs. 50,000 enough to rehabilitate a family which lost everything in the course of forced displacement? Today, there are two settlements in Hapachara: one is of those IDPs who have received the Rs. 50,000 and the other is of those who are still fighting for the package. There is little difference between the two camps.

One of the most pertinent questions arising here is whether the Indian state considers rehabilitation and resettlement as a ‘reward’ or ‘entitlement’ (L.J. Bartolome, C. de Wet, H. Mander, V.K. Nagraj 2000). It is unfortunate that instead of accepting rehabilitation as an entitlement or right for displaced people, the government rather offers it as a ‘reward’ against the sacrifice made by the displaced persons. The government remains indifferent even in cases of humanitarian crisis. The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (iDMC) observes that in Assam and Tripura, food shortages and lack of health care leave the internally displaced in acute hardship. Its report further stated that “The state governments say they have no money to provide relief to the displaced population and that they depend on support from the central government,” (iDMC 2007). The central government seems even more reluctant; despite the formulation of its National Resettlement and Rehabilitation Policy in 2007, it continues to grossly fail in addressing the issues and concerns of the large numbers of IDPs in the country.

International organizations like the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, Norwegian Refugee Council and other human rights organizations have been asking the Indian government to enact relevant law in accordance with the United Nations Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement (Azad 2013). Principle 18 of the said UN Guidelines says, “At the minimum, regardless of the circumstances and without discrimination, competent authorities shall provide internally displaced persons with and ensure safe access to a) essential food and potable water, b) basic shelter and housing, c) appropriate clothing and d) essential medical and sanitation.” This holds the state duty bound to provide relief and rehabilitation to IDPs, which is seen as their basic rights. Those bodies have also recommended the Indian government to form a constitutional body like the National Human Rights Commission or the National Commission for Women to protect the rights of internally displaced persons. A government that can shamelessly say it has no money to feed those ill fated people however, can hardly be expected to formulate such law or make any competent body.

It must be asked though, how much money is actually needed for the resettlement and rehabilitation of IDPs? Is India poorer than Azerbaijan, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Colombia, Croatia, Georgia (Ahmed 2008), all of which have made the necessary legal and constitutional arrangements for their IDPs? On October 7, 2014, the IDPs of Hapachara camp marked the 21st anniversary of their displacement. Is it really too expensive for the world’s largest democracy to do its duty to its own people?

References

Ahmed, Shahiuz Zaman. “IDPs in South Asia: Issues and Challenges.” In Internally Displaced Persons in South Asia, by Shahiuz Zaman Ahmed Debamitra Mitra, 3-22. Agartala: Icfai University Press, 2008.

Azad, Abdul Kalam. “The Internal Displacement Persons: Issue Roared in Assam Assembly.” Eastern Crescent, May 2013.

Citizens’ Rights Preservation Committee (CRPC), Assam. “Approach Paper (National Convention on D Voter in 2011 in New Delhi).” Citizens’ Rights Preservation Committee (CRPC), Assam, 2011.

Goswami, Sabita. Along the Red River. New Delhi: Zubaan, 2013.

Goswami, Uddipana. “Nobody’s People: Muslim IDPs of Western Assam .” In Blister on Their Feet: Tales of IDPs in India’s Northeast, by Samir Kumar Das, 176-188. Sage, 2008.

Guha, Amalendu. Jagaran (Char Chapori Sahitya Parishad Asom), 2011.

Hassan, Sajjad. “Summery of Assam Visit (Un-published).” September 2014.

iDMC. India: Large Number of IDPs are unassisted and in need of Protection. Switzerland : iDMC Norwegian Refugee Council, 2007.

L.J. Bartolome, C. de Wet, H. Mander, V.K. Nagraj. Displacement, Resettlement, Rehabilitation, Reparation, and Development. Cape Town: WCD Thematic Review I.3, 2000.

Rajagopalan, Swarna. Peace Accords in Northeast India: Journey over Milestones. Washington: East West Centre , 2008.

Abdul Kalam Azad is a final year MA student at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences and a volunteer with Aman Biradari, a people’s campaign for a secular, peaceful and just world.