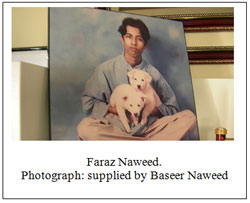

Journalist and activist Baseer Naweed encountered the opaque operations of Pakistans intelligence agencies when his son Faraz Ahmed was kidnapped, tortured and killed outside his office during a major campaign against corruption. Five years and various threats later, he works for the Asian Human Rights Commission in Hong Kong, but is no closer to the truth.

The Guardian UK

Tuesday September 8th 2009

My whole life I have been an activist. I was a student leader, then joined trade unions, then became an investigative journalist. I wouldnt say that my son was following me; in fact he would tell me I was making compromises. Hed probably have called himself an anarchist back then.

My whole life I have been an activist. I was a student leader, then joined trade unions, then became an investigative journalist. I wouldnt say that my son was following me; in fact he would tell me I was making compromises. Hed probably have called himself an anarchist back then.

When he was 14 he started writing on his own, though at that time I didnt know it. In fact he was like an ordinary Muslim, going to the mosque and praying; it was only when he started arguing about religion and the existence of God with his mother and grandmother that I realised he was a different kind of man.

Faraz was very fond of reading Einstein and Stephen Hawking, and at the time of his death he had just started studying philosophy at university. He would spend days reading books in second- hand book shops, using his pocket money at night to eat dinner with the garbage collection boys hed sit with seven or eight. Once I saw him and asked what he was doing and he said: I have to learn about how other people live.

I was the community organiser of a big campaign at the time. The Lyari Expressway project would displace 300,000 people from a slum, and the government didnt have any right to do it. We fought and we got a historical resettlement deal each family got an 80-square-yard plot and 50,000 rupees (£364) something like this had never happened in Pakistan. And the size of the plots was good. Here in Hong Kong only the very wealthy have that much space.

This all took three years, but corruption had also started in the use of public funds and we were fighting that too. I was seen as a real troublemaker. I was told that President Musharraf once said to the governor: You cannot handle that man with white hair (I was not colouring my hair in the way Musharraf did).”

During this time I was being threatened regularly. They would call and say that I was against the army and its chief, Musharraf; that we will kill you, or you wont be able to walk on your legs. I told them to go ahead. But my son used to take my mobile phone some evenings and he too would pick up these calls and get threats, though he didnt tell me.

I presented an Urdu radio program on FM103 called Current Affairs. It was November, I was at the station and people had mentioned mysterious movements around our office. Then my son came to get his fees for university so I told him that he could read out some of the poems we were broadcasting that day by Urdu poet Joan Ellia, who he loved. Then he went to the washroom, but he didnt return. It was only the next evening when we started to really worry.

The day after that, moments before the news program somebody came and said, there is a body of a man outside. I said: Look, Im going to start the program, why are you telling me? But after, I went down. In those days there were two gangs who were always fighting and killing each other, but I thought that the young man looked educated, not like a militant, so I asked the police to check his pockets. He was so mutilated. His whole jaw was out and there was blood oozing from bullet wounds in his back and his neck was broken, I think because of being thrown from an upper window. It was not possible for me to think that it was my son. Then the card came out and, yes, it was him.

You cannot imagine. At the official hospital we sat there for two or three hours with the body of my son out in the open, waiting for an autopsy. They kept delaying and making excuses. A philanthropist organisation eventually encouraged me to bury him, but the police refused to get the body themselves. The mullah and other Muslim people said that it was too late and that the prayer had been completed, so I felt I had to bury him.

A few days after the burial, when our house was full of people, one of my female relatives smelled burning. We rushed upstairs to find all Faraz’s photos and some of his writing on fire in the bath; now we have just one or two photos left. Really, these people wanted to punish me.

At first the people were protesting on my behalf but I discouraged street protests and I pursued the case with a human rights organisation. But although the [government] made a committee to probe it, they appointed a higher official who was notorious for putting sensitive cases into cold storage. We had four or five head investigating officers in less than one year, all transferred from the case or suspended. They have given us nothing. And now no evidence is left, my friends in the courts and the police have told me that.

After two days we went up to the top floor of my office building and we found blood stains. So we told police to take a sample of them and they said they would do it. But because I was suffering from depression so bad I could barely talk, barely stand in those days, it was some time before I asked again. Then they said the stains had been washed away because there was rain. So what can you think? After twenty days my other son was dragged out of his school bus and beaten he was 14 and told to tell his father not to pursue this case.

Ive even given them permission in writing to exhume the body. I talked to the superintendent of the civil hospital who assured me that he would get permission from the judge and do the autopsy himself. That was in 2005. Before leaving the country I had gone to see the officers to help some friends of my son who were being interrogated, and the officers said: We have this report that it was a suicide. I asked them what finding they had to prove this and they said: It’s just our own conclusion.

I think there is no hope that the government will solve this case because the military is still so powerful.

Here in Hong Kong my family feels safer and I have more freedom and more space. After my son was taken there was no real hope in life, we were just living for our remaining two children. Working with a direction to help expose other human rights violations gives me energy, and patience and strength.

Once I was in a mood to take revenge, but to whom will I do this? Its not possible. But last year we did a lot of good work supporting the lawyers in Pakistan as they campaigned against Musharraf, to protect the rule of law and have the Chief Justice reinstated, which eventually happened.

I still work very closely with journalists, NGOs and lawyers in these kinds of cases. Still, really I feel like Im only living now for my other two childrens dreams I hope that some of them have survived.

Baseer Naweed was interviewed by journalist Jo Baker.

To support this case, please click here: SEND APPEAL LETTER

SAMPLE LETTER