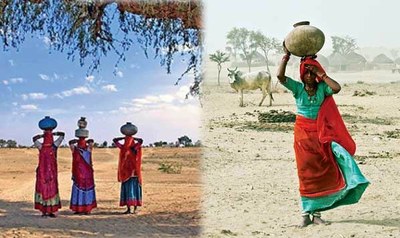

Cyclic drought and rise in temperature due to climate change has again brought havoc to the people of Tharparkar. The worst affected being women and children.

Shahid Hussain

Tharparkar is one of the 23 districts of Sindh province and is spread over 77000 square kilometres. It is the continuation of ancient Indian Desert – the largest portion is in Rajasthan at one side while Desert of Cholistan is at its rear side. According to a consensus held in 1998, Muslims constitute almost 59 per cent of the population whereas the Hindus constitute of the rest of 41 per cent of the total population of the region. Cyclic drought, famine and sand storms are very common in this particular region and the settlers of this region mainly depend upon nature’s blessing, the rain.

The recent cyclic drought and rise in temperature due to climate change has once again brought havoc to the impoverished people of serene desert Tharparkar – mainly affecting women and children who face malnutrition of the highest order. It is high time that concrete measures are taken on a long-term basis to contain this crisis instead of ensuring doles of charity to the great desert where human and livestock population is 1:4. According to IG Forests, Syed Muhammad Nasir, if camel breeding is given a priority and local species that naturally thrive in the vast desert are planted on a massive scale, the problem of severe malnutrition could be contained and women and children can live a healthy life.

The recent cyclic drought and rise in temperature due to climate change has once again brought havoc to the impoverished people of serene desert Tharparkar – mainly affecting women and children who face malnutrition of the highest order. It is high time that concrete measures are taken on a long-term basis to contain this crisis instead of ensuring doles of charity to the great desert where human and livestock population is 1:4. According to IG Forests, Syed Muhammad Nasir, if camel breeding is given a priority and local species that naturally thrive in the vast desert are planted on a massive scale, the problem of severe malnutrition could be contained and women and children can live a healthy life.

“Camels can sustain life without water for several days and there are hardy species in Tharparkar that can not only provide fodder to livestock but also ensure food security to people, including women and children who suffer the most when there is drought in Tharparkar,” said Nasir.

Thousands of non-governmental organizations are active in Pakistan but Thar Rural Development Programme (TRDP) stands distinct amongst them. Its leadership hailing from local people is not only aware about the problems faced by the people residing there but has a will to organise them and bring about a change through participatory development. Dozens of projects are run by TRDP not only in the vast land of Tharparkar but also in Dadu, Hyderabad and other districts.

The TRDP has been especially helpful in providing solace to the victims of 2010 flooding, essentially caused by climate change and the heavy rains of 2011 that displaced tens of thousands of poor people in Sindh. Enjoying the support of donor agencies and the Sindh government due to its commitment, TRDP teams have worked day and night to distribute relief goods to the flood and rain victims.

One of the most acute problems faced by the people of Tharparkar is the non-availability of water. During cyclic droughts the inhabitants have to migrate to barrage areas along with their livestock in order to sustain themselves which is a cumbersome journey. Livestock happens to be the main source of livelihood for the poor people of this region. And in order to bring a drastic change the availability of clean water is a must.

For the sake of providing the people with safe water, TRDP in collaboration with the government of Pakistan has embarked on several projects with positive results. Drip irrigation and use of solar energy has been successfully tried in the desert by the organisation.

According to Peter Bosshard, Policy Director International Rivers Network (IRN), an independent, non-profit organization based in California, Pakistan very urgently needs to switch over to drip irrigation in order to use water in a sustainable manner and to avert looming water crisis. In other countries, 90 per cent of agriculture is based on drip irrigation.

With 40 per cent water being wasted in Pakistan, essentially due to mismanagement, access to freshwater in the country has fallen from 5,200 cubic metres per capita in 1947 to less than 1,000 cubic metres in 2006, making it one of the most parched nations in the world.

“Everybody tells me that corruption is pervasive in water sector in Pakistan and when you see the projects that make no social, environment and economic sense go forward, the phenomenon can only be explained by corruption.

“The World Bank after 1995 stopped funding large dams because public opinion had turned against them and the bank knew it had to tread very cautiously. We have been more successful in stopping some of the worst projects from going forward, but we have not managed to re-direct them to support positive solutions which can reduce poverty and protect the interest of people. In order to save River Indus from dying a slow death, a development model was needed that would cater to the needs of people instead of a privileged class,” shared Peter Bosshard in an interview in 2006.

Scientists have pointed out that the glaciers of the Tibetan plateau are vanishing so fast that they would be reduced by 50 per cent every decade in the wake of global warming.

In village Wandhanjo Wandu, Nagarparkar, one was amazed to find that a local farmer Mohabat is cultivating his 6-acre land with solar energy and is earning Rs300 daily through the sale of vegetables alone.

According to Mohabat, “I had this piece of land since long but it was lying barren due to the non-availability of water. I used to work as a hari (peasant) in Thatta district and was barely able to make my ends meet. Now I am self-employed and earn pretty well.”

Mohabat grew tomatoes, eggplants, onions, chillies and sunflower on his field. He fetched Rs 20,000 from the sale of tomatoes alone and yield in sunflower was 40 maunds per acre that he sold for Rs1, 800 per maund. Similarly, the yield in onion was 60 maund per acre. He fetched Rs250 for every maund of that commodity.

Mohabat grew tomatoes, eggplants, onions, chillies and sunflower on his field. He fetched Rs 20,000 from the sale of tomatoes alone and yield in sunflower was 40 maunds per acre that he sold for Rs1, 800 per maund. Similarly, the yield in onion was 60 maund per acre. He fetched Rs250 for every maund of that commodity.

“I use drip irrigation to conserve water and am a happy man now,” he said.

Known as Lift Irrigation, the project on which Mohabat works has been initiated by the organisation and supported by Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund (PPAF). The total cost of the project is Rs 8,81,526 with a TRDP share of Rs1,78,926 and PPAF share of Rs7,02,600.

“Had I used a motor to lift water I would have needed at least 10 litres of diesel that would have been very expensive,” informed Mohabat.

Similarly, in a village called Singharo, some 55km from district headquarter Mithi; poor villagers are fulfilling their requirements of drinking water through seven solar panels powering pumps that lift underground water. At least 60 houses of the small village of 2000 people are not only getting their thirst quenched courtesy to solar energy but are also making money through the sales of tomatoes, brinjals and other vegetables.

Again the project has been a collaboration of TRDP and PPAF. The solar pumps work for 10 hours between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. every day and women are seen collecting water from the water tank.

The well is 170 feet deep. Previously women in the village would fetch water from the deep well through camels and donkeys which was a tedious job. Now solar energy is being used to do the job which has made the lives of women a lot easier.

Apparently, installing solar panels for the impoverished people of Tharparkar appears to be a costly affair but if one keeps in view that the great desert of Pakistan always has a blazing sun, one is bound to agree with enthusiasts relying on non-exhaustible sources of energy.

“Drip irrigation is the future of Pakistan. It means we have to learn water conservation and this can improve the lot of poor farmers,” said Dr. Sono Khangharani, former Chief Executive Officer TRDP in an earlier interview.

“In 90 per cent areas of Tharparkar we can avail solar energy that can play a vital role not only in provision of electricity, cultivation but can also help in job creation, poverty alleviation and in giving a boost to local economy. The use of solar energy in Tharparkar will also result in reverse migration,” explained Dr. Khangharani.

After PPAF extended a helping hand in 1999, TRDP established a Community Physical Infrastructure Unit (CPI) in Tharparkar’s district headquarter Mithi under the supervision of qualified engineers and initiated several projects to tap ground water in the arid zone of Sindh. However, paucity of funds remained the major obstacle.

It introduced Deep Hand Pump (Afridive), Reverse Osmosis desalination systems in solar water pumps in Tharparkar and Dadu districts. In a small village Rane-ji-Wandh in Tharparkar solar water pump has been installed at a well that quenched the thirst of 40 families besides their other domestic needs.

Since the system has been successful in the past, TRDP went for installing the system in other villages too. In short, despite odds and constrained resources TRDP in collaboration with its partners has surely proved that only drip irrigation and use of solar energy is the solution in our water-starved country.