Manipur, a state in the northeast of India is in national news since the past two decades. The state remains in news for all the wrong reasons. Stories from Manipur are not that of the miraculous economic growth the country has been achieving despite the worldwide recession. They have nothing to do with the information technology revolution which has contributed immensely to India’s claim to become a future superpower. Neither do these stories have anything to do with the democratic experiment that the country has undertaken with élan.

The stories from Manipur are that of despair. They are of extrajudicial executions, abductions by state agencies and armed insurgents, of custodial rape and that of torture. These stories have turned the citizens into hapless creatures, caught in a ruthless cycle of self reinforcing violence.

Among these countless stories of distress is one that of hope and despair alike, although of a gigantic proportion. It is about the extraordinary courage of an ordinary woman. It is an epic tale of a democratic political protest unparalleled, perhaps, in human history.

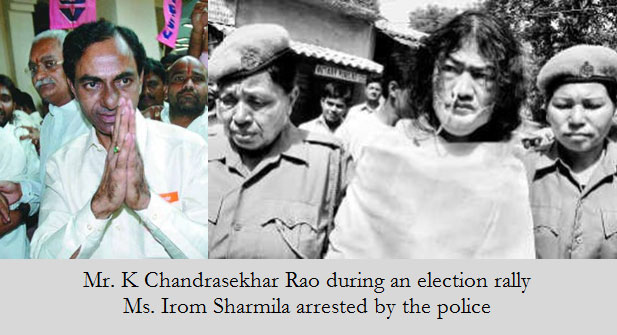

The story is that of Ms. Irom Sharmila, who entered the tenth year of her fast on 5 November this year, demanding a repeal of the draconian Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958 (AFSPA) imposed in Manipur since 1980. Section 4 of the Act gives the security forces a statutory right to kill with impunity on mere suspicion. Impossible in worlds largest democracy one may think. And all Sharmila is asking for is the repealing of this law.

The government is yet to pay heed. Unfortunately, it seems, so is the case with the country’s citizenry, including its media. The media decided to look the other way when the Director General of Police in Manipur, Mr. Y. Joykumar, claimed that his men have murdered 260 persons this year, all terrorists of course. It did not bother to investigate the killings, abductions and disappearances. In short, the media is least bothered about bringing out the facts behind these cases to the people. In that, the media is complicit in the crime.

Andhra Pradesh is another state that remains in news, albeit mostly for good reasons. The story of Andhra has been that of ‘India Shining’. Andhra is a state that has achieved prosperity and has found a place of pride as one of the most well governed states in the country. It is a state competing with its neighbours like Karnataka for the envied position of becoming the engine of India’s economic growth.

Andhra is probably the only state which had a chief minister who preferred to be referred to as the Chief Executive Officer, and not a mere chief minister. It is also one of the states in the country that the multinational corporations could ignore at their own cost. Andhra has hosted international personalities like President Bill Clinton and Mr. Bill Gates.

The stories about the visits of important foreign dignitaries were all over the media, leaving nothing to imagination. The public were fed with each and every detail of the visits of these dignitaries, down to the point of, in which room of what hotel they stayed. The media discussed at length the unprecedented growth of Hyderabad, Andhra’s capital city, of its pubs and malls. And of course these malls are second to none, not even to those in the western countries.

The media dutifully brought out the perceptions the expat executives had of Andhra. It carried the stories of their life in the capital city, what they liked as well as what they did not. The business pages of all national as well as regional dailies were filled with stories of the two-point lead Andhra is continuously maintaining over the national average.

While covering all these stories, the media conveniently forgot to tell the public about what was happening just two hundred kilometres away from the state’s capital. With a lone exception, perhaps that of Mr. P. Sainath from The Hindu, not a single journalist in the country was looking into the sorry state of affairs prevailing in Telangana, a region in Andhra.

Life has become tougher for the farmers, for handloom owners and workers alike, and many were committing suicide in Telangana. People are migrating from Telangana due to starvation and hunger. The media did take notice, when an over confident CM/CEO called for early elections, assured of his victory, and lost it miserably. Media attributed his defeat to the poverty in Telangana, but did not take long to get back to its usual interests.

Telangana, meanwhile, kept simmering with anger. The people of the region felt betrayed by the state government. They rightfully perceived that the reason for the underdevelopment of Telangana is the non-allocation of resources due to the region. The state’s politicians invested resources to other richer parts of the state like Hyderabad. So a demand for a new state emerged. The demand was rooted not in ethnic nationalist discourse, linguistic identity or any such framework, but purely in the political economy of development.

The governments, both at the state and central level should have taken note of the simmering public anger. But they chose to ignore the concerns and aspirations of its citizens. The governments rather decided to sit on the issue playing petty electoral games to the extent that the political party in power contested the elections for the state assembly with an alliance with the Telangana Rashtra Samiti (TRS) promising to carve out a new state, Telangana, if they win. They won the election, but failed to keep the promise.

This led to a further escalation of anger in Telangana. Mr. K Chandrasekhar Rao, the leader of TRS, who was gradually losing his popularity among the people due to his flip flops in policies, sensed the opportunity and went on a fast unto death. The announcement proved to be the proverbial last nail. The people supported the fast, and the demand for a new state. The anger simmering within was now boiling, hitting at anything that came in its way.

The public response was of two extremes. On one hand the people started committing suicide demanding for a new state, and on the other, they protested destroying public and private property. Within ten days of the fast the government realised that it has lost the plot, and that it cannot contain public anger.

With the deterioration of Rao’s health, things went out of control. By the eleventh day of the fast, the government has had it. The government conceded to Rao’s demand. Thus the government fulfilled a promise, albeit not on its free will.

This brings the debate about the binaries India operates in. It raises questions about the government’s reasoning. Why did the government rush to act on a fast unto death running just over ten days and not on one which has entered its tenth year?

It does not question the legitimacy of Rao’s demand. The fast did represent the wishes and aspirations of the people of Telangana. But so does Sharmilas. Rather it would not be wrong to argue that the issues Sharmila has been raising are far more serious and have a bearing on the very notion of democratic governance and not merely on the politics of development.

After all, the security forces cannot kill anyone with impunity in Andhra. Though Andhra has its own dubious record of human rights violation, its people at least can go to the courts. Finally, the people of Telangana did not feel like being occupied by a foreign army in their soil.

The answer lies in the sad reality of the time, that the government of India has long stopped listening to democratic movements. Peaceful movements like the Narmada Bachao Andolon were not only humiliated by the government, even the judiciary short shifted them. The victims of the Bhopal gas leak, the biggest industrial catastrophe of the world, are yet to get justice. The perpetrators of that crime are still free. The organisers of the 1984 pogrom against Sikhs have actually been rewarded rather than being punished. Those responsible for the Gujarat riots against the Muslims have been occupying constitutional offices instead of serving terms in prison.

This is the primary reason behind many of the erstwhile peaceful states of India slipping into a self reinforcing cycle of violence and counter violence. Despite all this, the union government appears to be in a state of complete denial of its role in bringing things to this level. The polarised binary of violence versus non violence is the government’s creation and the government has been pushing the people into armed rebellion by ignoring non-violent means. Telangana is a stark reminder of the fact that the government would not listen to the people until they resort to violence.

Yet, it is not all over for the Indian democracy yet. The government can very well put its act together by addressing genuine demands, wishes and aspirations of the people and the process can begin with an effort of democratising itself as well as its law enforcement agencies. The need of the hour is a reengagement of the government with its citizens, within the framework of respect a democracy should give to its citizens. All this would require a government that would put an immediate end to war mongering by many of its own agencies, including the home ministry and would rather try achieving a rapid de-escalation of tensions between and within many of the warring parties.

The government has responded well by addressing the concerns of the people of Telangana, it could do better by addressing those of Manipur. Until the government does that, the media should come out of its slumber and start doing what it is supposed to. It should reclaim its position of being the watchdog of the citizenry and not the mouthpiece for the high and the mighty.