THAILAND: Four-year anniversary of imprisonment of Somyot Prueksakasemsuk

Last Thursday, 30 April 2015, was the four year-anniversary of the imprisonment of Somyot Prueksakasemsuk, a longtime labour rights activist and human rights defender. On 30 April 2011, Somyot was arrested on allegations of violating Article 112 of the Criminal Code. He was held for six months of pre-trial detention and then hearings in his case were held between 12 November 2011 and 3 May 2012. On 23 January 2013, the Criminal Court in Bangkok convicted Somyot Prueksakasemsuk of two violations and he was sentenced to ten years in prison in this case, as well as to one year in prison in relation to a prior case. The Appeal Court upheld the original decision on 19 September 2014. At present, Somyot is further appealing his verdict to the Supreme Court. Since he was first arrested and placed behind bars, like the majority of detainees under Article 112, Somyot has been consistently denied bail, despite 16 bail applications being submitted. The Asian Human Rights Commission calls for the immediate release of Somyot Prueksakasemsuk and all others imprisoned for exercising their freedom of expression.

Article 112 of the Criminal Code stipulates that, “Whoever, defames, insults or threatens the King, the Queen, the Heir-apparent or the Regent, shall be punished with imprisonment of three to fifteen years.” Although this measure has been part of the Criminal Code since its last revision in 1957, there has been an exponential increase in the number of complaints filed since the 19 September 2006 coup; this increase has been further multiplied following the 22 May 2014 coup.

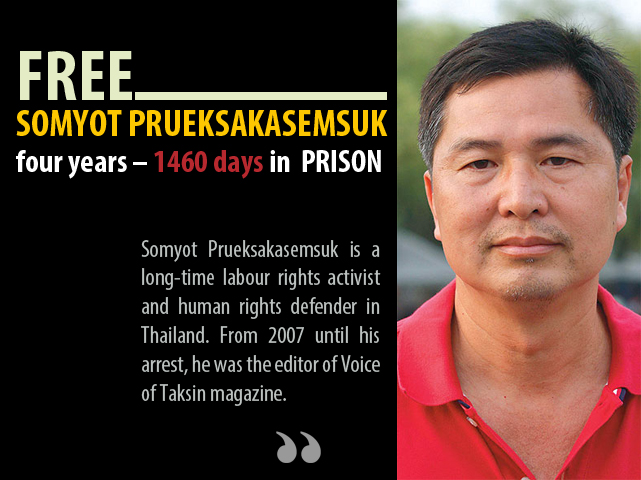

Somyot Prueksakasemsuk is a long-time labour rights activist and human rights defender in Thailand. From 2007 until his arrest, he was the editor of Voice of Taksin magazine. In Somyot’s case, the Article 112 charges stemmed from allegedly allowing two articles with anti-monarchy content to be published in Voice of Taksin magazine. The prosecution argued that his work in printing, distributing and disseminating two issues of the magazine which contained content deemed to violate Article 112 was itself an equal violation of the law. As in other lese majeste cases, the Court’s decision turned on the issue of intention. In the abbreviated decision released on 23 January 2013, the Court offered this interpretation of Somyot’s guilt: “The two Khom Khwam Kit articles in Voice of Taksin did not refer to the names of individuals in the content. But were written with an intention to link incidents in the past. When these incidents in the past are linked, it is possible to identify that (the unnamed individual) refers to King Bhumipol Adulyadej. The content of the articles is insulting, defamatory, and threatening to the king. Publishing, distributing, and disseminating the articles is therefore with the intention to insult, defame, and threaten the king.” The implication of the Criminal Court’s argument here is that anyone involved in the editing, publishing, disseminating, or distribution of material that is judged to have the intention to defame, insult, or threaten the monarchy, is criminally liable.

At the time of the initial decision, the Asian Human Rights Commission warned that it was an ominous warning to anyone involved in publishing, distributing or selling print or other media (AHRC-STM-027-2013). What made the conviction particularly important was that it demonstrated how the enforcement and interpretation of Article 112 was both uneven and highly political. Writers and publishers would not know that they have crossed the invisible line demarcated by the law until the police knock on their doors to take them away. The decision heralded the creation of an atmosphere of fear and a new set of limitations on the free expression and circulation of ideas, particularly those deemed to be critical or dissident. More than two years after the decision, and over eleven months after the 22 May 2014 coup by the National Council for Peace and Order, this atmosphere of fear has been consolidated.

Four years – 1460 days — have passed since Somyot Prueksakasemsuk was arrested. This is 1460 days too long.

The Asian Human Rights Commission calls for the immediate release of Somyot Prueksakasemsuk while his case is pending at the Supreme Court. The AHRC further calls for the immediate release of all other individuals facing charges or convicted of violating Article 112 and related laws. Until this happens, the AHRC will continue to closely follow all other cases of alleged violations of Article 112 and encourages all others concerned with human rights and justice in Thailand to do so as well.