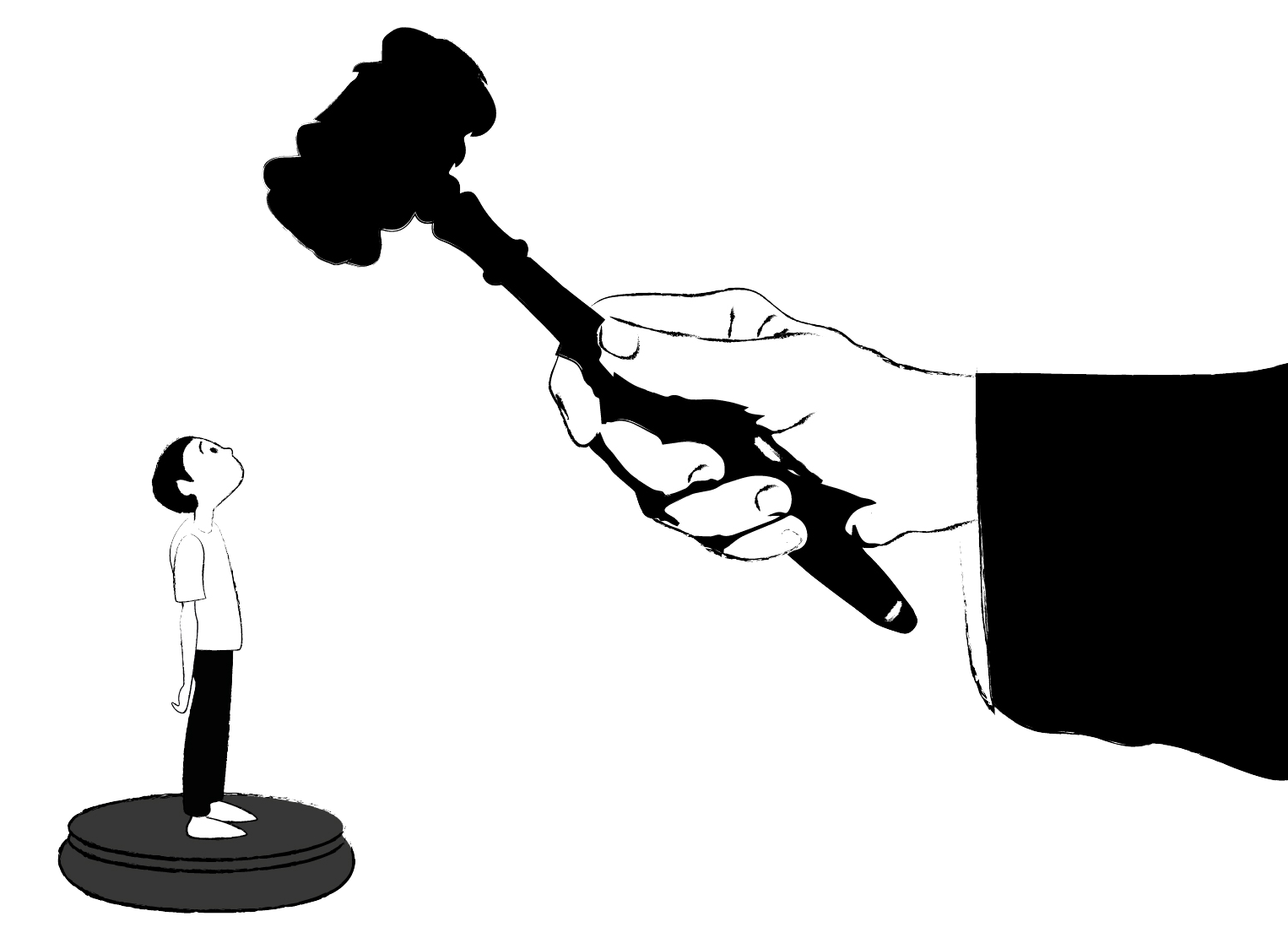

The true character of a society is revealed in how it treats its children – Nelson Mandela

The Juvenile Justice (Amendment) Bill 2014 was not deliberated by the Parliamentary Standing Committee, as it strongly opposed the amendments made to it; despite this, the Union Cabinet went ahead and passed the bill in the Lok Sabha (Lower House of the Parliament) on 7 May 2015. It is now bound to come up for discussion and voting in the Rajya Sabha (Upper House of the Parliament) in the upcoming Monsoon Session.

The Juvenile Justice (Amendment) Bill 2014 was not deliberated by the Parliamentary Standing Committee, as it strongly opposed the amendments made to it; despite this, the Union Cabinet went ahead and passed the bill in the Lok Sabha (Lower House of the Parliament) on 7 May 2015. It is now bound to come up for discussion and voting in the Rajya Sabha (Upper House of the Parliament) in the upcoming Monsoon Session.

The amendments to the Bill have little focus on child protection and well-being and most notably provide significant alteration in the degree of punishment to be handed to a child committing “heinous” crimes. These amendments were decided purely based on public and political pressure, with the Nirbhaya rape case being a key factor changing the outlook towards a child less than 18 years of age.

It is not a sudden revelation that the country is unsafe for women and children; the government has done nothing to prevent such crimes, but is quick to act on amending bills that form only a small part of a larger picture. Given this, can one say that the Bill represents the nation heading in the right direction?

State role & working structure of the bill

In an attempt to improve the reviewing of cases, Section 15(1) of the Bill states that the Juvenile Justice Board shall review pending cases every three months, with increased frequency of sittings, and may recommend the constitution of additional Boards. Section 15(2) states that a high level committee will biannually review the number of cases pending with the Boards, the nature of pendency and so forth, and, as per (Section 15(3)) this information shall also be furnished to the state government on a quarterly basis.

The role of the state is ambiguous, however, and every state functions differently. The success of the provisions will depend on whether the state will act and direct orders on such pending case reports, or whether the information will just pile up in their offices as per routine.

Maharashtra has the highest pendency of juvenile crime cases, nearly 16,000, with the Juvenile Justice Board in Pune District alone struggling to clear 1,205 pending cases. The pace is slow, with only 36 cases having cleared from 1 April 2012 to January 2013. No doubt, some of the state juvenile boards function well and put in great effort towards speedy trial and clearing pending cases, but the major obstruction of little manpower in the Juvenile Justice Boards needs to be cleared. Every state has appointed very few members to the Boards, not at par with the number of pending cases. Without the required manpower, it is simply impossible to dispose of cases even if cases are heard day and night.

In some states, the functioning of the Juvenile Justice Boards is rusty, due to political recruitment of Board members, who have no knowledge of child psychology, and no experience or background of child-related issues. Not only do such members lack interest, but they also show insensitivity towards children. According to a report by the Asian Centre for Human Rights (ACHR), in Assam, replies received from Juvenile Justice Boards under the Right to Information Act have shown not a single review of the pendency of cases being conducted by the Chief Metropolitan Magistrate or Chief Judicial Magistrate.

The Juvenile Justice Bill is thus impressively articulated on paper, but not in practice. The Bill also highlights compulsory registration of child-care institutions or housing, due to the repeated violence and sexual abuse faced by children in these places. Although creating a database of children living in such institutions is a good step, it will not end violence. The lack of an active monitoring system and uniform protocol for the inspections of child-care institutions is visible in every state.

How can one forget the horrific case of rape and sexual violence inflicted upon 100 girls living in a registered child-care institution known as Apna Ghar, Haryana, by the caretakers and outsiders in 2012? This institution was regularly inspected by the state Child Welfare Committee, but the case was only reported when three teenage girls escaped to New Delhi and filed a complaint.

This is because of the outrageous nature of these inspections; at every visit to such institutions, committees expect to be entertained by the children with dance, songs, or any other talent, as though they are clowns. Insensitive committee members do not seem to understand that from a deprived background, these children need an ear to listen to their agony, not see them as free entertainment. With the whole inspection day wasted on such nuisance of merriment, there is no time left to actually review the institutions’ working conditions.

The Bill has made no improvements to the appointment of the Inspection Committee or its functioning. Rather than stating any clear protocols or accountability that the Inspection Committee should undertake, the Bill simply has some vague directives on submitting an inspection report to the state or district Child Protection Unit. Without any firm legal guidelines, states choose to appoint members based on political influences. These members are usually ineffectual and uninterested, particularly if they are already holding positions in other governmental departments. Ultimately, there is nobody who is willing to promote the well-being of the children. It is just a policy that has no life to it but is shiny enough for window dressing.

Obsolete facilities and way of functioning

While India has a growing Information Technology industry that contributes significantly to the national GDP, government departments still lag behind in the use of modern technology. The “new is silver and old is gold” mentality hindering the use of modern devices leads to classic situations, such as delays in child rape hearings, as the concerned authority cannot furnish the child’s medical report from a hospital located in a different area. Such delays could have been avoided if faxing facilities were used at the right time; a visit to any state department however, will disclose the kind of machines they use or don’t use. This indicates the lack of motivation for officials to use modern devices as a tool for smooth administration.

The infrastructure of child housing institutions is in poor condition. Children are made to adjust in tiny spaces. A shelter home run by Drone Foundation, an NGO in Haryana, houses 14 children in two rooms. Such facilities do not encourage children to live or even think about a normal life. It is more like transferring children from one slum to a better slum with concrete walls. Budgets are definitely allocated for such infrastructure, but development is nowhere to be seen.

The use of out-dated Social Investigation Reports are absurd in this age, keeping unquantifiable factors such as whether the child has family or moral values, to ascertain if the child is capable of crime or not. A child being born in a family of drunks and thieves doesn’t seem to be a good enough factor to analyse her capability of committing a crime; it is not the child’s fault of being raised in such a family.

The report is made by a probation officer who is not required to have a background of psychology or expertise in child related issues. It is bizarre to think that such an officer also has the authority to decide a treatment plan for a child based on these reports. In fact, one probation officer not only works with children under the Juvenile Justice Act, but also with other subjects under the Domestic Violence Act as well as other acts. The efficiency of such an officer is hence watered down and his impact minimal. The Bill gives little importance to appointing a psychologist who veritably has more knowledge in preparing a child’s Social Investigation Report.

A custom more honored in breach than observance

While it is accepted that the State has the capabilities to protect and promote the well-being of citizens, it is bewildering for Section 73 of the Juvenile Justice (Amendment) Bill to protect the State for action taken in good faith. This is particularly so when the people making decisions “in good faith” are not necessarily armed with the qualifications to do so, such as the Inspection Committee, the Juvenile Justice Board members, or the probation officers. Furthermore, the Judiciary’s interpretation of “good faith” can be quite perplexing. The thousands of cases pending in courts against the State for action under good faith is another indicator undermining Section 73 of the Bill.

The Bill gives supremacy to the Juvenile Justice Board to decide the course of a child’s life as the Board deems fit. There is no surety, however, that the board will make decisions based on facts and evidence, considering that a child, if sent to adult prison, will not have a second chance at life. It contradicts the entire ideology of reforming a child in conflict with law. There are no concrete statistics to validate the number of children that have been reformed so far. Usually, those children, after serving their time in juvenile homes, actually go back to becoming hard core criminals.

Although the Bill tries to comply with various international standards on the promotion of child rights, it also violates the United Nation Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice by placing children on trial as adults. While preparing this Bill, in violation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, the opinion of children was not taken into account; and yet, the Bill provides that they should be treated as adults while committing “heinous” crimes.

Ultimately, there is little substance to the Juvenile Justice (Amendment) Bill, 2014. With little sense of direction, the Bill seems to have been made under political pressure and public outcry in order to calm the outrage and maintain the ideological balance of power in politics. The functions of the Juvenile Justice Board and the Child Welfare Committee is evidently low on performance, with 175 million children in India still marginalised, 144 million deemed to be destitute, 25 million orphaned, and 40,000 juveniles in conflict with law, living in institutes.

The government needs to reflect on its own shadow and understand that the Bill should be more proactive rather just being a well-articulated piece of legislation.