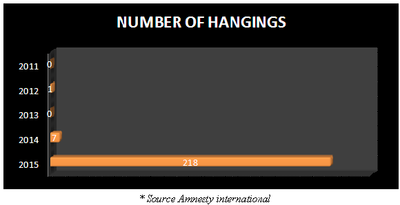

The number of hangings in Pakistan has already crossed the 200 mark in 2015, and there are still about four months left in the year. If killing human beings were a race, Pakistan is winning hands down. And still there is room for improvement.

An estimated 8,000 people, the largest in the world, are on death row in Pakistan. If the government, were to decide to up their execution rate even more and kill all the death row convicts this year itself, State executioners will have to hang 667 people daily.

It is not unlikely. For, to appease the real rulers of the land, the propped up civilian rulers have no qualms about unleashing a spate of judicial, quasi-judicial, or extrajudicial murder. The 21st Amendment to the Constitution has already been instituted to assist ruthless State terrorism.

On March 17, Pakistan executed 12 people, the highest number of executions in a single day in almost a decade. Within no time this record was broken on April 21, when 15 people were hanged. Of the provinces, Punjab has taken the lead; 170 executions have taken place in Punjab in 2015.

In December 2014, Pakistan lifted the moratorium on executions, which had been in place since 2008, in the wake of the Taliban attack on a school in Peshawar that killed more than 150 children. The death penalty was initially reserved for terror convicts, but on March 10 of this year it was extended to all capital crimes, including kidnapping and murder.

Of those executed, perhaps only two to three have been terrorists. Under the guise of tackling terrorism, the government is using ruthless power to terrorise the whole society through these executions, taking shelter behind a constitutional amendment.

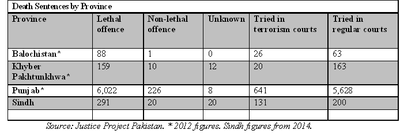

The lifting of the moratorium on the death penalty was always going to be more of a populist move than a deterrent. And, this has proved to be the case. With poor reputations and labyrinthine and archaic procedure of testimony and evidence, the Anti Terrorism and Session’s Courts have been passing death sentences. Rampant miscarriage of justice that results due to confession obtained through torture is the basis for these courts to hand down death sentences. These courts are blind to justice and norms. They have been handing death sentences to minors and even the mentally and physically challenged.

Take the case of Khizar Hayat, a schizophrenic, whose mental state deteriorated due to 17 years spent on Pakistan’s death row. Due to relentless efforts of the Justice Project of Pakistan (JPP), a group working for prisoners on death row, and the District and Dessions Judge Tariq Iftikar Ahmad, the execution of Khizar’s death warrant was delayed to allow for a proper medical evaluation. But the State remains determined to hang him till his death.

Khizar’s death warrant arrived at a time when the State of Pakistan was already receiving much condemnation from the international community for the execution of Shafqat Hussain, who was a juvenile at the time of the crime. Khizar’s death warrant is in violation of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which Pakistan ratified in 2011. The UN Commission on Human Rights adopted resolutions in 1999 and 2000 urging countries that retain the death penalty not to impose it “on a person suffering from any form of mental disorder”. Additionally, Section 84 of Pakistan Penal Code excludes from criminal punishment any person demonstrating “disorder of his mental capacities”.

Another case of miscarriage of justice cost Aftab Bahadur his life. Aftab was put to death in June, despite evidence that proved he was a minor when he was convicted of murder in 1992. Though he recanted his statement, which he later claimed was made following torture, he was executed.

Though Khizar is temporarily saved from the gallows, another disabled Abdul Basit, a paraplegic, faces the gallows. The wheelchair bound prisoner at Lahore jail, Basit, 43, was convicted and sentenced to death for murder in 2009. In 2010, he contracted tubercular meningitis in prison. The prison authorities did not provide him sufficient health care, which left him paralysed from the waist down. Despite a government-appointed medical board having confirmed the continuing severity of his condition, last month a “black warrant” was issued for Abdul Basit’s execution.

Commenting on these cases, Harriet McCulloch, Deputy Director of Reprieve’s Death Penalty Team has said: “It is deeply disturbing that Pakistan’s authorities are trying to go ahead with these two cruel and unnecessary executions. There is surely no justification for trying to hang a man with the severe disabilities from which Abdul Basit clearly suffers – nor for killing Khizar Hayat, who is severely mentally ill and has little understanding of his fate. Killing these two seriously ill men will do nothing to improve safety and security in Pakistan and will further damage the reputation of Pakistan’s criminal justice system.”

Pakistan is one of eight countries in the world, namely China, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Iran, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, United States, and Yemen, which has since 1990 executed prisoners that have been under 18 years old at the time of commission of crime.

To comprehend how Pakistan has joined this illustrious list, a brief chronology on death sentences in Pakistan is in order. President Mr. Asif Ali Zardari on 9 September 2008 issued an indefinite moratorium on execution of death sentences for prisoners on death row. The moratorium ended on 14 November 2014 when Mr. Muhammed Hussain, a soldier, was hanged for murder at Central Jail Mianwali.

On 17 December 2014, after the Peshawar school attack, the State lifted the moratorium for terrorism cases. Finally, on 10 March 2015, Pakistan lifted the moratorium on the use of capital punishment in the country entirely.

On 28 April 2015, Pakistan carried out its 100th execution since the moratorium was ended for the death penalty in December 2014. On June 14, the Pakistan government announced a temporary reprieve for death row prisoners during the month of Ramadan.

The lifting of the Moratorium on the execution of death sentences in a country where the criminal justice system is marred by miscarriage of justice and corruption is a complete travesty. The civilian as well as the military courts are sentencing people without following due process. Even the façade of the rule of law has taken a back seat as the State gropes in the dark to deter terrorism with judicial and quasi-judicial terror.

Without tackling the root cause of terrorism, i.e. poverty, unemployment, illiteracy, and increasing radicalisation, hope for reformation is wishful thinking. Drawing distinction between the good Taliban and the bad Taliban while the innocent are hanged serves no meaningful purpose, other the perpetuating cruelty.