by Laksiri Fernando

“Autobiography is about change; it narrates a series of transformations. This is an expectation we bring to any autobiographical text.” – Carolyn Barros

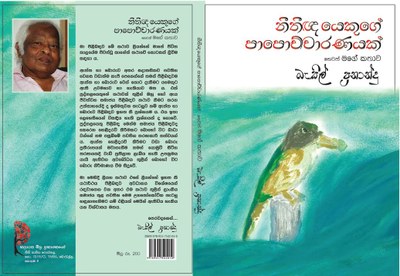

When I picked Basil Fernando’s Nitignayekuge Papochcharanaya hewath Mage Kathawa(A Confession of a Lawyer or My Story), admirably written in excellent Sinhala, I got what I reasonably expected. It is a narrative of Basil’s transformations from a curious village boy from Palliyawatta, Wattala, to an internationally reputed human rights advocate now living in technologically advanced city of Hong Kong. Why he lives in Hong Kong is part of the story.

When I picked Basil Fernando’s Nitignayekuge Papochcharanaya hewath Mage Kathawa(A Confession of a Lawyer or My Story), admirably written in excellent Sinhala, I got what I reasonably expected. It is a narrative of Basil’s transformations from a curious village boy from Palliyawatta, Wattala, to an internationally reputed human rights advocate now living in technologically advanced city of Hong Kong. Why he lives in Hong Kong is part of the story.

The first episode of his last chapter titled “The Death List” ends with a sentimental comment on his father.

“It became clear to me from most of what I heard from others that my departure from the country greatly affected my father who was already becoming weaker and weaker because of age. I also came to know later that a frequently asked question by him was whether I would ever come back.”

Loss of dear ones, temporary or permanent, by departure, incarceration, disappearance or death was part of the unfolding tragedy in Sri Lanka of that time in late 1980s. The crime he had committed was to appear as a lawyer for a sister of someone who was suspected to be a ‘JVP terrorist.’ Of course Basil had appeared for several other human rights cases during that time to add to his misfortune. Anyone who exactly wants to know why he was forced to leave the country as an exile should read through the previous chapter twelve fittingly titled “Injustice Created through Law.”

Law and Injustice

What is more important in this chapter is the contradictions and paradoxes within the legal system that he explains succinctly. The legal and the court system is supposed to protect the liberty of people under normal circumstances. But under Emergency and under the Prevention of Terrorisms Act (ACT) this is not at all the case. The whole of the judiciary was in a crisis. The judges and even the lawyers came under immense pressure and they were virtually helpless. He has outlined several of the contradictions and tragedies.

- Under normal circumstances, the effort of a good lawyer is to get bail for the client as soon as possible. But under the prevailing situation, the remand prison was safer than bail or otherwise the client could have possibly disappeared after release.

- The police used to submit incredible reports to keep people incarcerated. However challenging them could have amounted to being accused of abetting terrorism. No one was ready to take that risk.

- To prevent possible disappearances, the clients or their families were asked to take unusual procedures. One was to petition higher officials as much as possible with much details of whereabouts of the person under arrest and let the arresting authorities also know about the petitions.

All these discussions in the biography are directly important to the prospective or the practicing lawyers in the country. No one could be sure at what point the country might fallback to such a situation even in the future. After all, the biography is titled as a ‘confession of a lawyer.’ What might be interest to any reader is the last episode that he has related.

Basil has appeared for a client who has killed his wife quite unknowingly in his insanity. When the case was up, the Judge has called Basil to his chamber and asked how he would plead for his client and pointed out that he could give a lenient punishment if pleaded guilty for ‘homicide in insanity’ or ‘culpable homicide.’ The Sinhala term that Basil has used is ‘Sawadya Manushya Gathanaya’ (false homicide) which I am not aware of. That is how it was settled. The point of the story is to argue that most of what happened during late 1980s amounted to a similar insanity on the part of the whole of the Sri Lankan society.

“There was no major difference between the mental status of all of us living in the country and the mental status of the client that I represented,” he has noted.

The style of the autobiography is innovative. The substantive chapters from chapter nine are divided into several episodes each one impressively giving snap shots of different stages of his metamorphosis into the present status. Being a poet, other than being a lawyer, Basil has related these stories in a lyrical manner. On the contrary, being a crude political scientist, or a claimed one, I am definitely not in a position to appreciate fully the value of his literary eminence.

Village Background

Let me however focus on the first few chapters on his ‘village background.’ As he has openly admitted, he has quite an influence from Martin Wickramasinghe in many ways. Before commenting on more controversial ideological influences, there is a clear resonation of Ape Gama (My Village) particularly on the first few chapters. Can he be criticized of imagining an ape gama through Palliyawatta? He cannot be.

Many of our post-independence first generation of Sinhala educated perhaps tried to imagine the same during our young days. I did the same quite unsuccessfully in my own ‘village’ at Moratuwella, and couldn’t unfortunately gather the minute details of what Basil has gathered on flora and fauna or more precisely on various types of Ibbas (tortoises) orIssas (prawns). But what differs my experience from his experience perhaps is in relation to caste and class.

In his depiction of “Internal Divisions within a Village” in chapter two, the caste system predominates and any particular mention of class divisions is conspicuously absent. Perhaps that was the exact situation in his village but this is substantially different to my experience. Of course we knew about the existence of certain families belonging to certain castes but they were not despised because of that fact in any manner. I was not even aware of my own caste until I came of age. Moratuwa undoubtedly was at the forefront of the capitalist development and the main division in my own locality was between the ‘rich’ and the ‘poor’ and not between different castes. This is one reason why Moratuwa became prominent for leftwing radicalism as the great majority obviously belonged to the poor.

What might be questionable in Basil’s analysis is that the caste system and the antecedent ideological backwardness are depicted as some evils that came after the influence of Hinduism, as he says, after the 8th century. According to historians (i.e. K. M. de Silva), the caste system prevailed in ancient times of Anuradhapura and even there were Candalaswho were confined to do the menial work.

The genesis of the caste system was vocational and service. The basis was not primarily religion or ideology but the political economy. When there were major disruptions or final breakdown within the traditional political economy, undoubtedly the caste system became uglier socially than when it was working. This is exactly what happened under colonialism even continuing after independence. All the examples he has given shows that the so-called high castes were using the ‘stigma’ as a weapon in their social competition or to demean others when they were advancing socially.

Transformations

Basil has always been a conscientious bloke as I knew him. His social convictions had come quite early. As he says, he was influenced by the SWRD Bandaranaike moto which was popular at that time: “the primary duty of man is to serve mankind.” When he was in grade nine, he has joined the seminary to become a De La Salle Brother, if I am not mistaken. Perhaps this was in 1959. He was trained at Mutwal and then in Penang, Malaysia, for this purpose. Then came a rupture even before he returned to Sri Lanka in 1964.

The first influence was the Second Vatican Council (1962) which was a renewal of the catholic doctrine more towards the needs and aspirations of the people wherever the Church worked. Basil also recounts the influence of a Dutch Catholic Priest, Fr. Henk Schram, who influenced him and others greatly even before the Vatican II. All these were towards working for the people and particularly the poor. Then came his exposure to the leftwing ideas during his study at Aquinas College for his university entrance. It is not clear however from the narrative that when he abandoned the idea to become a Catholic Brother, perhaps much later.

His study as a student of law at the University of Colombo appears to be relatively uneventful although he is critical of all what the Faculty offered him as ‘legal knowledge.’ I have no reservations on the matter whatsoever. He is critical of the professors, the (law) students and particularly of the curricula. It was in the midst of his university days that the JVP insurrection of 1971 had taken place but he was quite safe and immune. There are several key statements to this undisturbed effect.

Without becoming a practicing lawyer Basil has become an English teacher at the Vidyodaya University after his law degree. This phase seems to be quite a radical one in his life. Apart from teaching English, he had become a ‘teacher in revolution’ for the masses. For some years, he was associated with a leftwing Trotskyist organization of which I was a founder a few years ago. But by the time he joined, however, I had left the organization because of my milder or moderate policies. We crossed our paths very narrowly. All indications were about his devotion to the cause, until he became disillusioned and left the organization for good. However, his experience within the organization must have helped him to become a lawyer with a social conscience later.

The experiences that he has related as a lawyer and the cases referred to as episodes in the evolving saga are useful insights for anyone who wish to understand the breakdown of rule of law and the predicaments of the judiciary in the country amidst social and ethnic conflicts. His story spanning for over sixty years, intermittently relates major events and incidents from the Bandaranaike era to the Eelam war in the North through two insurrections in the South.

Another tragic story that he relates is the court case of Kuttimani and his killing in the prison custody.

His later international experience, particularly in Cambodia during the peace process and reconstruction, supply more useful insights in understanding the tragedies of a country facing protracted social and ethnic conflict/s. In the case of Sri Lanka, his critical eye is unhesitatingly focused on the Police and its excesses.

A Critical Comment

There cannot be much doubt that the story that Basil Fernando relates is part of the common story of everyone in Sri Lanka. Much of it, however, is his own interpretation quite useful for anyone to understand the events, developments and underlying causes.

As Professor Sunanda Mahendra has stated in a review, “This, I felt, is a remarkable effort in the search for the truth, and nothing but the truth.” He has also said, “As a reader, I felt that the readings of Basil Fernando are fused with a certain sense of religio-sensitivity which depicts the needs to express the inexpressibility.”

I am not sure, however, whether I can completely agree with what he says about the ‘truth and lie’ (aththa saha boruwa). In his Preface, he has argued that there is something called ‘the eternal difference or contrast between truth and lie.’ Second, he has argued that ‘one can only understand the above clearly if one intends and capable of understanding the truth and lie about himself or herself.’ This appears to me a very subjective endeavor although he has admitted that ‘this is not a problem that can be solved easily.’

It may be true or need to be respected that if Basil is a believer of truth and lie about this world. In my case, I am not, and quite skeptical about absolute truths except what the Buddha has said about the four noble truths. However there are valuable historical, social and political propositions and conclusions that humans have arrived at both as targets and means to achieve them. Otherwise, most of the interpretations that we make about events and developments are subject to controversy and different points of view.

I am particularly skeptical about his final conclusion or the concluding paragraph which says referring to Martin Wickremasinghe’s Bawatharnaya that “The conclusion that I have arrived at is the evolution of the social crisis that Sri Lanka facing today cannot be understood separated from the major transformations in the country around the twelfth century.” Apparent historical inaccuracy apart, one can even criticize Basil for interpreting history through the narrative of Sinhala nationalism. It is this narrative which considers all what came from Hinduism or South India to be detrimental to the glorious Sinhala civilization. Perhaps this mistake or orientation is a result of Basil’s effort to be religiously sensitive to Buddhism or the way he wanted to understand ‘what is Sinhala Buddhism.’

Note: All the quotations are my translations from the original text.

Laksiri Fernando, BA (Ceylon), MA (New Brunswick), PhD (Sydney), is a former Senior Professor in Political Science and Public Policy at the University of Colombo and currently a Visiting Scholar at the University of Sydney in retirement. He has served Vidyodaya University, University of Peradeniya and the University of Colombo in different times teaching Political Economy and Political Science. He was a Japan Foundation Fellow in 2005-6 and was Fellow at the Universities of Ryukoku, New South Wales and Heidelberg. He served as the Secretary for Asia/Pacific of the World University Service (WUS) in Geneva and Executive Director of the Diplomacy Training Program (DTP) at the University of New South Wales. Primarily a researcher on human rights and ethnic conflict, his publications include Human Rights, Politics and States: Burma, Cambodia and Sri Lanka; Political Science Approach to Human Rights, Police Civil Relations for Good Governance and Ethnic Conflict in the Global Context among others. He was Director of the National Centre for Advanced Studies (NCAS) and a Director of the Colombo Stock Exchange.

Laksiri Fernando, BA (Ceylon), MA (New Brunswick), PhD (Sydney), is a former Senior Professor in Political Science and Public Policy at the University of Colombo and currently a Visiting Scholar at the University of Sydney in retirement. He has served Vidyodaya University, University of Peradeniya and the University of Colombo in different times teaching Political Economy and Political Science. He was a Japan Foundation Fellow in 2005-6 and was Fellow at the Universities of Ryukoku, New South Wales and Heidelberg. He served as the Secretary for Asia/Pacific of the World University Service (WUS) in Geneva and Executive Director of the Diplomacy Training Program (DTP) at the University of New South Wales. Primarily a researcher on human rights and ethnic conflict, his publications include Human Rights, Politics and States: Burma, Cambodia and Sri Lanka; Political Science Approach to Human Rights, Police Civil Relations for Good Governance and Ethnic Conflict in the Global Context among others. He was Director of the National Centre for Advanced Studies (NCAS) and a Director of the Colombo Stock Exchange.