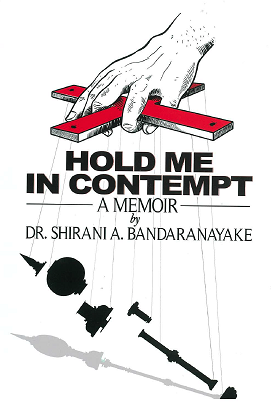

SRI LANKA: What happens to the people happens also to judges, lawyers, and others

A comment on the memoir of Former Chief Justice Dr Shiranee Bandaranayake entitled “Hold Me in Contempt”

Basil Fernando

Attorney-At-Law

This memoir by former Chief Justice Dr. Shirani Bandaranayake on the (now nullified) impeachment is a significant contribution to the cause of promoting the independence of judiciary in Sri Lanka. Its significance lies in the fact it exposes the truth about what really has happened to the judiciary as an institution within the context of changes brought about by way of the constitutions of 1972 and 1978, and the practices that have developed as a result of these constitutional changes. The memoir makes it starkly clear that the separation of powers, independence of the judiciary and respect for rules of natural justice are no longer a part of the Sri Lankan legal system, although many who are involved in the administration of justice may proclaim these as part of their credo. The contrast between truth and illusion is very clear when looking at the actual narrative of what took place by way of pressures exerted on the Chief Justice, and the ‘so-called-impeachment’ story.

This memoir by former Chief Justice Dr. Shirani Bandaranayake on the (now nullified) impeachment is a significant contribution to the cause of promoting the independence of judiciary in Sri Lanka. Its significance lies in the fact it exposes the truth about what really has happened to the judiciary as an institution within the context of changes brought about by way of the constitutions of 1972 and 1978, and the practices that have developed as a result of these constitutional changes. The memoir makes it starkly clear that the separation of powers, independence of the judiciary and respect for rules of natural justice are no longer a part of the Sri Lankan legal system, although many who are involved in the administration of justice may proclaim these as part of their credo. The contrast between truth and illusion is very clear when looking at the actual narrative of what took place by way of pressures exerted on the Chief Justice, and the ‘so-called-impeachment’ story.

She speaks touchingly about the relationship she had with her parents, who created a deep impression on her on the need to be faithful ones conscience and be truthful. Judging from her account of her resistance to having anything other than a strictly professional relationship with the executive, and the resistance to various pressures that came about related to the conduct of Judicial Services Commission, and, perhaps above all, in the manner in which she resisted all attempts to pressurize her to voluntarily quit her job to save the embarrassment of the executive for dismissing her, clearly demonstrates that she was faithful to her belief in acting on the basis of her conscience.

Personal Conscience and Social Conscience

The fundamental issue that arises here is as to whether, particularly in moments of national and a social crisis, is it enough for a judge (or, indeed, for anyone engaged in public life) to merely do their particular job within the framework of faithfulness to one’s conscience, while not addressing the structural framework within which they conduct their affairs, when that framework opposes the very principles that they are trying to defend. For example, the issues related to the separation of powers and the independence of judiciary, the need to follow the principles of natural justice in giving a proper hearing to person whose conduct is being examined, and even the very notion of a fair trial, need to be addressed. When these necessities are structurally removed, is it possible for one to carry out one’s duties on the basis of one’s personal conscience? Are not the issues of the absence of the structural recognition of the very notions on which one is trying to conduct one’s affairs a relevant factor in assessing how to function under these circumstances, and important to being faithful to one’s conscience?

1972 and 1978 Constitutions

The structural removal of the idea of separation of powers took place when the 1972 constitution was adopted. At the debate, all the prominent spokesmen for the government of the time quite categorically stated that the separation of powers principle had been displaced the removal of the possibility of the judiciary to challenge any of the decisions by the legislature. This they called the supremacy of the parliament. It removed the basic structural framework of the Soulbury Constitution, which was made on the basis of the general principles of liberal democracy.

The following two quotations are illustrative:

“In our view, the doctrine of Separation of Powers has no place in our Constitution. The National State Assembly is the supreme instrument of State Power and exercises the legislative power of the people, the executive power of the people, and also the judicial power of the people.”

[The Associated Newspapers of Ceylon Ltd., (Special Provisions) Bill Decision (Decisions of the Constitutional Court of Sri Lanka, Vol. 1 (1973), at p. 53; affirmed in the Administration of Justice Bill Decision (Decisions of the Constitutional Court of Sri Lanka, Vol. 1 (1973), at p. 67))];

And

“We are trying to reject the theory of Separation of Powers. We are trying to say that nobody should be higher than the elected representatives of the people, nor should any person not elected by the people have the right to throw out the decisions of the people elected by the people. Why are you saying that a judge once appointed should have the right to declare that Parliament is wrong? That you must have judges do the job of judging is true. We do not want to be judges.”

[Mr. Felix R.D. Bandaranaike, the Minister of Public Administration and Local Government, as quoted in MRA Cooray, Judicial Role under the Constitution of Sri Lanka An Historical and Comparative Study (Lake House Investments Ltd. 1982) p. 224]

In 1978, the Executive President’s position was created and their role was meant to be higher than that of the legislature. This enormously significant transformation was created after government MP’s had been made to give undated resignation letters. This created a rather ridiculous situation in the country regarding the operation of constitutional law. Within that transformation, the Supreme Court lost the position it had under the Soulbury Constitution. When studying for postgraduate degrees abroad, and also when teaching law, Dr Bandaranayake may have acted on the belief that all the principles of liberal democracy were also part of the legal tradition in Sri Lanka. She may have also attempted to practice such beliefs in her time as a Supreme Court judge and a Chief Justice. But doing that was to ignore the actual transformation of the legal framework in the country, which had been brought about not only through constitutional changes, but also by widespread and deliberate practices.

Neville Samarakoon, Sarath Nanda Silva and Mohan Peiris

The struggle between J R Jayawardena as president and Neville Samarakoon as the Chief Justice was basically on that issue. Neville Samarakoon, who had been a Senior Counsel for many years within the framework of law introduced by the British, seemed to have thought that he could function within that same framework after the adoption of the 1978 Constitution too. He had to pay a heavy price for believing that illusion

The Chief Justice that was appointed under Chandrika Kumarathunge’s government had no such illusions. He went all the way, not only adapting to the new situation but also doing everything possible to protect the executive president and the presidential system. It was for that reason that he virtually undermined all the procedural laws and also undermined the legal profession. Thus, there was no conflict between the Executive President and Chief Justice Sarath Nanda Silva, as they both knew that they were dealing with a completely new set of ‘principles’ and not on the basis of the basic norms of a liberal democratic system.

Judicial Power- Judicial Role and Killings of Persons after Arrest

Besides those changes happening within the judiciary itself, there were other changes of even greater importance. They clearly showed that the judicial function had been removed even in decisions involving the life and death of citizens. The killing of arrested persons in their tens of thousands happened under emergency laws.

The greatest privilege of the judiciary is that it alone can decide on the life and the liberty of the individual. This is particularly so when the issue is one of life and death. What came to be known as enforced disappearances is the usurpation of judicial power by the executive, which then hands that power to anybody it wishes, including the lowest ranking officers of the police or the military. All applicable legal requirements, including the need to hold postmortems for suspicious deaths, were removed and certain ranks of police officers were given the power to order burials, and they had no obligation to keep any record of what they did.

Leaving other matters aside, this issue alone is sufficient to prove that Sri Lanka lost the ability to claim the existence of an independent judiciary, by allowing arrested persons to be killed and disposed of by the executive, with no access to judicial protection via fair trials, due process or rights. Judicial power was thus challenged in a far more fundamental way than by arbitrary impeachment through that practice of the authorized killings of persons who had been arrested and were in custody.

These are just a few things that show that it was not only by constitutional changes but also through widespread practices that the role of the judiciary and judicial power were enormously undermined in Sri Lanka, and there was no attempt at all to undo that situation.

What we saw during that period was not judicial resistance to the undermining of their role and of judicial power itself, but, as the cases of Sarath Nanda Silva and Mohan Peiris clearly demonstrated, there was an adaptation to whatever that the Executive President wished to do.

Judicial impeachment treated as a practical joke

It is within such a background that the impeachment story should be looked at. While the demand of the Chief Justice and her lawyers was for due process and the observance of the normal procedures that would be followed in a matter as serious the removal of Chief Justice in more serious jurisdictions, the fact was that, in Sri Lanka, such a situation did not exist. The Mahinda Rajapakse government treated the whole affair of the removal of the Chief Justice simply as a practical joke.

This practical joke consisted of arbitrarily getting the required number of members of parliament to sign a petition with charges that they hardly knew anything about, then giving the highest possible publicity to these charges, and then appointing a group of politicians – the majority of whom were of the same governing party – to be judges on the alleged misconduct of the Chief Justice, and then engaging in amateur dramatics to make it impossible for the Chief Justice and her lawyers to perform any useful function during the inquiry, and then getting their resolution while ignoring all objections that were made by the opposition.

The intention behaving as though it was all a practical joke was starkly clear: it was to pressurize the Chief Justice to resign on her own and to make it quite clear to her that the justice she expected was not going to take place, and that the executive will do whatever it wants, and that all attempts to insist on innocence was a futile exercise. It was to her enormous credit that she did not play her part in that game. The public impression was therefore that what was being done was illegal, void and completely unjust.

Injustice is not an abnormal affair in Sri Lanka anymore. It is what the people are facing throughout the country at every instance, whether they belong to the majority community or minority communities. Even the killings of over 250 people on Easter Sunday did not lead to any kind of justice. Thus, it appears that justice is simply an irrelevant matter in Sri Lanka.

What the impeachment story brings to the notice of the public and the international community is this stark fact. Will the people, and even the judges, acknowledge this reality, or would it be more convenient to believe in the illusion of there being separation of powers, independence of the judiciary and a possibility of fair trial in Sri Lanka on any matter of significance to the executive? These illusions are from a past in which there were possibilities of such practices based on liberal democratic norms. So long as these illusions persist, they will only lead to greater catastrophes.

Former Chief Justice Dr Shirani Bandaranayake has done a great service in producing this memoir. It is to be hoped that in the years to come she may undertake to examine the history of the loss of the independence of the judiciary in Sri Lanka, and the historical developments that have led to the possibility of turning the whole impeachment procedure into a farce. She has made a good beginning. However, if this work is to create possibilities for change, much more needs to be done, with deep self-searching by those had the opportunity see things with their own eyes,

This is the way to be faithful to her father’s calling to be truthful to one’s conscience. This is not only for those who supported her throughout the impeachment, but also for all Sri Lankans, who are condemned live without liberty and who have lost their precious institutions.