PHILIPPINES: Negros and its people through my eyes–inequality before the law (Part 4)

Danilo Reyes

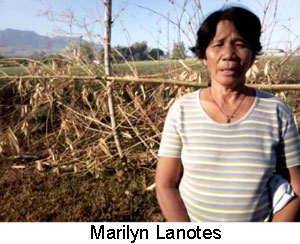

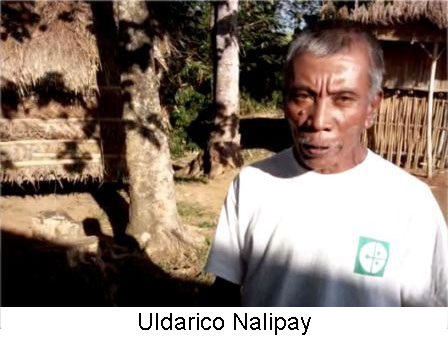

The story of two elderly farmers, Marilyn Lanotes, of Hacienda Tres Hermanos and Uldarico Nalipay, of Hacienda Manuela, both in Cadiz City, Negros Occidental, are just two of the many examples that can illustrate the inequality before the law between farmers and landowners and how the application of the law is abused to favour the latter.

Marilyn had been working for her employer, Rafael Lopez Vito, since the early 70s. Vito owns the 154 hectares of land on which Marilyn and others had been employed as farm workers. The minimum wage that the law requires the employers in this region to pay their employees is some Pesos 218 per day but Marilyn and her fellow workers only receive Pesos 167.

The workers endured this nonpayment of salaries and the benefits they were due for years until they decided to complain and demanded the payment of the differential. This is also one of the reasons that prompted them to file a petition to have the land they had been cultivating covered under the land reform program with the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) in Bacolod City in February 2007. The DAR is a government agency responsible for the implementation of the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP), a law intended for the distribution of land to landless farmers and tenants.

The workers endured this nonpayment of salaries and the benefits they were due for years until they decided to complain and demanded the payment of the differential. This is also one of the reasons that prompted them to file a petition to have the land they had been cultivating covered under the land reform program with the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) in Bacolod City in February 2007. The DAR is a government agency responsible for the implementation of the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP), a law intended for the distribution of land to landless farmers and tenants.

However, as a result of the DAR’s failure to promptly resolve their petition and after their employer resorted in terminating their employment, the farmers were forced to cultivate 31 of the 154 hectares purely as a means for subsistence, like growing food and supporting their families and children in their daily needs. They planted sugarcanes, intercrops vegetables (these are crops that are planted in between the rows of sugarcane to maximize land usage) and root crops by March and April in 2009.

This ended up with sixty two of the farm workers being prosecuted for malicious mischief and usurpation of property by June and July 2009 respectively in regular courts. These are criminal offenses under the country’s penal code that involves acts in which one destroys and/or takes possession of another person’s property. Under the arbitration rules of the DAR, any complaints or dispute arising from the implementation of CARP should be heard in the offices of the DAR (the original jurisdiction) and not the regular courts. However, the prosecutors in this case nevertheless pursued filing the cases in court.

Also, when the farm workers sought the assistance of the local police in October 2009 to prevent other farm workers that their landlord had hired from other towns from harvesting the sugarcane that they had planted, the police did not take action. They even told them that they as complainants had no right over the property. The duty of the police should have been solely to maintain the law and order and any dispute should have been settled with the DAR for arbitration as to who should harvest and owns the crops; but the police nevertheless arbitrarily passed judgment in favor of the landlord. Thus, the farm workers that the landlord had employed were able to harvest the crops.

Also, when the farm workers sought the assistance of the local police in October 2009 to prevent other farm workers that their landlord had hired from other towns from harvesting the sugarcane that they had planted, the police did not take action. They even told them that they as complainants had no right over the property. The duty of the police should have been solely to maintain the law and order and any dispute should have been settled with the DAR for arbitration as to who should harvest and owns the crops; but the police nevertheless arbitrarily passed judgment in favor of the landlord. Thus, the farm workers that the landlord had employed were able to harvest the crops.

Therefore, Marilyn and her fellow workers who had worked hard planting sugarcane, spending money from their own pockets to fertilize the land and worked hard to weed the land to ensure the crops would have a good produce ended up having nothing. Thus, the farm workers had lost their jobs, had to endure a lengthy and expensive legal battle over the ownership of the land and were prosecuted for cultivating the land they had been working for years. Some of the farm workers have, in fact, struggled between feeding their family and remaining in hiding for fear of being arrested, including Marilyn.

In another case, Uldarico Nalipay had been farming his land since 1960. He also chairs the Manuela Farm Workers Association, a group of farmers having 20 members who are also claiming ownership of a piece of land of 60 hectares. The property had already been covered for distribution under the CARP. Their employer had in fact ‘Voluntarily Offered to Sell’ (VOS) the property for the government to pay on behalf of the farmers.

Under the procedure, once the landlord had offered to sell the property to the government, the property would then be subjected to valuation to determine the cost of how much the government–to be represented by the Land Bank of the Philippines (LBP)–should pay the landowner before it would be turned over to the farmers. The landlord had not expressed opposition to the farmer’s petition to claim the land under the CARP. However, there had also been delays in the conclusion of this procedure prompting the farmers to plant sugarcane, root crops and vegetables covering 42 hectares which would have also been set aside for their subsistence.

Under the procedure, once the landlord had offered to sell the property to the government, the property would then be subjected to valuation to determine the cost of how much the government–to be represented by the Land Bank of the Philippines (LBP)–should pay the landowner before it would be turned over to the farmers. The landlord had not expressed opposition to the farmer’s petition to claim the land under the CARP. However, there had also been delays in the conclusion of this procedure prompting the farmers to plant sugarcane, root crops and vegetables covering 42 hectares which would have also been set aside for their subsistence.

One day, armed men employed by the landlord came to the village and destroyed the sugarcane, root crops and plants that Uldarico and his fellow farmers had planted. According to Uldarico, he saw the landlord in the company of police officers and soldiers. Since then Uldarico and his companions have been subjected to continuing harassment and intimidation, surveillance and monitoring by the landlord’s armed men and paramilitary groups deployed in the village during nighttime.

Uldarico decided not to file a complaint; not because he had waived his right or he did not know that he could do so, but because in a small village like theirs he knew full well he would end up complaining to the same police officers he had seen accompanying the landlord!

To his surprise, a week later he and his fellow farmers ended up being charged for robbery in band and qualified theft. Those charged, however, had not been given opportunity to know the nature of the charges or respond to the charges before the arrest orders were issued. These are offenses under the penal code.

Like Marilyn’s case, Uldarico had to go into hiding after the soldiers, carrying arrest orders from the court, started looking for him and those included in the charge. Under the law, those who had the authority to serve arrest orders from the court or effect arrest are the policemen; the soldiers and the landlord’s armed men have no authority to do so. Nevertheless, this has become the common practice by soldiers and the police tolerate these acts by waiving their authority and becoming subservient to them.

Apart from the soldiers, policemen and other armed men, the farm workers had also to endure surveillance and harassment by the paramilitary forces under the soldier’s control, the Citizens Armed Forces Geographical Unit (CAFGU). In this case, the actions by the soldiers, policemen and the armed men against the farmers had sown fear amongst the villagers that even to complain and to attend court could be hazardous.

These are the conditions in which the soldiers and police function contrary to their Constitutional duties and obligations–to serve and protect the people. These are notions and concepts that a poor farmer like Uldarico cannot comprehend because of the extent of the arbitrariness and illegalities.

Thus, Uldarico’s decision not to complain in this case should not be superficially dismissed as a person simply waiving his right or not knowing his rights and where and how to complain. It is simply that they know it will be a futile exercise.

Like most of the school children in Negros today, Uldarico only completed second grade; however, despite the level of his education he speaks and argues like any paralegal might. He knows his rights, what is due to them and what is wrong, despite having no formal education. He said that when he was a boy, he and his neighbors had to walk ten kilometers a day going to and from the school where they were studying.

The experiences of Marilyn and Uldarico demonstrate the extent to which the people in Negros have been struggling in their daily lives. They are people who have not only been subjected to control since birth, but are now being deprived of the opportunity of obtaining adequate education due to poverty. It speaks volumes for them that, regardless of all the setbacks they face they continue to fight and struggle to assert their rights and demand what is due to them.

Their compassion to struggle for their rights is an inspiration to all.

Please see the previous parts of these articles at:

PHILIPPINES: Negros Island and its people through my eyes (Part 1)

http://www.ahrchk.net/statements/mainfile.php/2010statements/2528/

PHILIPPINES: Negros and its people through my eyes–control begins at childhood (Part 2)

http://www.ahrchk.net/statements/mainfile.php/2010statements/2530/

PHILIPPINES: Negros and its people through my eyes–language is their freedom (Part 3)

http://www.ahrchk.net/statements/mainfile.php/2010statements/2537/