INDIA: Village structures perpetuate caste system

No Indian can imagine India without the caste system. Is it possible to have an Indian society without caste system and other social evils? In northern India, it is alarming to notice strong in-built age-old practices that ensure the caste system not only survives but thrives.

Land distribution and related traditions significantly contribute towards this social evil. Every village functions on a set pattern, namely:

Every village is comprised of settlements which are strictly caste-based. The upper castes, namely thakurs of the kshatriya (warrior) caste and brahmins (priest) caste, enjoy ownership of land, orchards and ponds. Persons belonging to the thakur, brahmin and sometime of vaishaya (merchant) castes, are generally educated and therefore most dominating in Indian society.

Most of the officers in government offices belong to the upper castes.

This structured village system is the biggest hurdle in educational opportunities for dalit children. Lack of education and rampant illiteracy among dalits cements the servile status of the dalits vis-a- vis the upper castes. Hence, the upper castes do everything within their power to prevent dalits from getting educated.

The upper caste children are indoctrinated in such a way that they consider it a virtue to engage the services of dalits in their fields, orchards and homes. They are made to believe that Dalit women exist solely for their pleasure and entertainment.

The village economy is based on the agricultural produce and almost all land belongs to the upper castes.

The roots of the caste system run deep and can be compared to a Banyan Tree. It is well structured and properly demarcated and though based on descent and occupation, is practically a class-structure. In order to justify their misdeeds and greed, the upper caste has developed the theory of varnashram, which later evolved into the caste system. They popularized this theory claiming it had divine origin.

Prevailing rituals, practices, economy and family structure in a village:

Uttar Pradesh of India has 97942 villages. 80% of its population lives in villages. 85% of those who live in the villages are Hindus. 60% of these Hindus are kshatriyas and brahmins (upper castes). A closer look at one village will help us understand other villages and villagers of Uttar Pradesh.

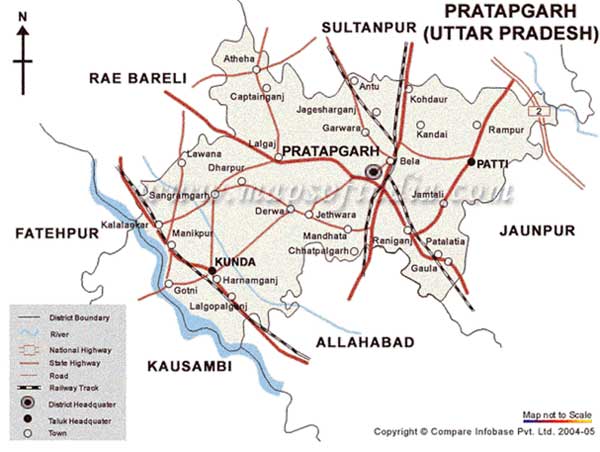

Bhupiyamau is a village in Pratapgarh district of Uttar Pradesh. It is situated at the intersection of the National and State highway and merely 5 kilometers away from the district headquarters.

| 1. | Total Population | 2152 |

| 2. | Total Population Males | 1107 |

| 3. | Total Population Females | 1045 |

| 4. | Total Scheduled Caste Population | 470 |

| 5. | Total Scheduled Caste Males | 240 |

| 6. | Total Scheduled Caste Females | 230 |

This village is inhabited by only three communities, namely brahmins, kshatriyas and scheduled castes. There is no presence of other backward classes in this village.

Let us see the land ownership pattern in this village.

The area of the village is 215.1 hectares. The total irrigated area is 180 hectares whereas 15 hectares is un-irrigated. The entire 195 hectares is owned by kshatriyas and brahmins. None of the Scheduled Caste (SC) owns any piece of land for agriculture. The SC occupies land on which their house stands. This is either provided or leased to them by a Kshatriya.

At harvest time, the SC is subjected to ill-treatment by the kshatriyas. This is because by and large kshatriyas compete with each other to have their crops harvested as early as possible. The entire harvesting is done by the SC who has to ensure the good pleasure of the Kshatriya.

That is why Kshatriyas pressurize them by beating and abusing them so as to get their crop harvested first. SC women are often victims of such violent assault. They are often paid in kind – food grain, rather than cash. Women have to work late night; which is hazardous, as they are molested and even raped by the land owner who, on the pretext of watching over the crops, generally sleeps in the thatched enclosure near the tube-well.

A close look at the geographical map and habitat of the village clearly reveals that the Brahmin settlement is strategically placed at the main entrance to the village on either side. A number of schools are found in the vicinity of the Brahmin settlement. The adjoining area is occupied by Kshatriyas followed by agricultural fields. The scheduled caste makes their abode in and around these fields. Therefore, they have no access to pasturelands to graze their cattle. They have no entitlement to the burial ground either, despite the fact that they are also Hindus. Hindus traditionally cremate their dead near the bank of a river. However, the lower castes are compelled to bury their dead due to sheer poverty and inaccessibility to village commons. Since there is no graveyard in the village, they sometimes leave the mortal remains in the river or cremate it on the river bank. Brahmins and Kshatriyas have their habitats close to the orchards and pasture lands; hence the lower castes suffer deprivation in every way.

This is how Bhagat, a thakur recounts his childhood experience:

When I was young, I shouldered the responsibility of managing the agricultural fields and harvesting the crop. I was barely 14 years old then. It was the summer season, and the month of June to be precise. The monsoons threatened to destroy the crop; hence I was anxious to harvest the crops. I approached the Dalit settlement many times to hire labourers, but with no success. They gave me false hope, saying they would come the next day, but they never turned up. I noticed that those who promised me they would come, were often working in the neighboring field. One evening, as I sat dejected outside my house, my father enquired as to what the matter was, and why the labourers had not come to harvest the field.

I simply said, They are working in our neighbors field. He laughed and said, You are worthless boy; you will never be a successful man. I have some advice for you, take it or leave it. Get your hockey stick or any other stick, and be prepared to use abusive language. As soon as you reach the settlement of the scheduled caste, beat up whomever you meet first. Then warn them, saying that if they fail to come to our field the following morning, you would meet them again along with your father. I did what I was told and to my surprise the labourers actually came to my field the following morning. When I returned home that evening, having harvested the crop, my grand-mother said, Son, Dhol, ganwaar, shoodra, pashu naari, ye sab taadan ke adhikaari (the drum, the uneducated, the dalit, the animal and woman deserve to be beaten) says our sacred book.

Thereafter, I successfully harvested the crop every year. As far as I remember, this was the first and last time I ever obeyed such advice.

Annually, we are expected to offer certain ritualistic prayers in every season and for every crop. Formerly, my father performed these rituals as it was his birthright to do so, he being the only son of his parents. Therefore, when I was a teenager, my father was anxious to share some of his responsibilities with me like, agricultural work and related rituals, attending social ceremonies in our village and other villages as well.

I noticed that the other youth in my village were more carefree, they did not seem to have responsibilities like I did. That is probably why I suffered from an identity crisis. Sometimes I felt superior, at other times inferior to them.

Once there was a cricket tournament in my village. I wanted to participate but on the same day I was asked to perform a ritual in the sugarcane field for a good crop. I refused and asked why my younger brother could not do it instead of me. Before I could even complete the sentence, I was slapped. I awaited the arrival of our family priest on an empty stomach till noon that day. Together, we went to the field for the ritual prayer. Hungry as I was, I requested him to hasten the prayer. The priest was annoyed and abused me, saying that I should remain quiet and not disturb him during prayer. After the prayer, we went home together. The priest was expected to cook for him and for me. I lost my patience. I took a cane from the field, hit him on his read and ran away.

He complained about me to my family. When I returned that evening my grandmother said, What the hell did you do? You will go to hell for hitting the Brahmin (priest) on his head. We have great for the brahmins.

I will go and call him. Only if he pardons you, will you enter the main gate. Finally, the priest came and forgave me.

The priest said, For the first time, in my life, a thakurs son abused me and beat me. This time I pardon you. But take care. If it ever happens again, you may be afflicted by leprosy.

Three cup practices in my home

Like most other thakur households, we have the three cups practice one cup is kept for the use of a dalit, another for the family, and the third for my use

I was the only non vegetarian in my family. That is why I was not permitted to cook and eat in our kitchen. I bought some utensils and started cooking non vegetarian food outside the house, where husk and other fodder was stored for our cows and buffaloes.

Some old and broken utensils meant for the use of dalits were also there. When ever any dalit visited us, she or he was served in those utensils. One day by mistake a dalit lady used my glass to drink tea. My grand mother saw this but did not say anything. When I came back, she told me that one of my glasses was used by a dalit lady. She instructed me to stow away my utensils in a bag, lest they be misused.

She gave me an old glass from the kitchen and asked me to keep it for my use. She told me to put back my glass with the other utensils.

I was very disappointed by this state of affairs. I told my grandma that if she considered me a dalit, then why she was trying to segregate me from other dalits. She said, You are not yet a Thakur. You will become a full-fledged thakur only after the ritual upnayan sanskaar. Once that is done, you are forbidden to eat non-vegetarian food. You still have time to enjoy a life, before you start living a disciplined life as a true thakur. Whenever I cooked non vegetarian food I was debarred from access to any other food that was prepared in the kitchen at home. The following day, I was permitted to get food from the kitchen only after I had bathed and performed other ablutions. However, I was not allowed to use my grandmothers utensils, as she was considered ritually clean, as she prayed daily. Others in the family only prayed occasionally. I had to avoid non-vegetarian food for a couple of days before engaging in ritualistic prayer.

When my sister got married, she was only vegetarian among her in-laws. When her in-laws visited us, I was very happy to have them join me in enjoying non-vegetarian food. One day my grandma tried to convince my sister to persuade her in-laws to quit non-vegetarian food. She replied very innocently, When our God and Goddess accept offerings of non-vegetarian food, how can I coax my in-laws to give up that. Today, my nephew is also a non-vegetarian, but my sister has no objection. She also cooks non-vegetarian food for her husband and son. When I ponder on what happens in these two families, I realize that in a thakurs household, women and children have no choice concerning their food. They are dalits ostracized within their own family.

My first experience of drinking liquor:

My grandfather was very fond of drinking liquor. Every evening he enjoyed drinking either with his friends or by himself. One day, I broached him with a question during one of his drinking bouts. What are you drinking? I asked. He replied, It is som ras nectar.

I said, Let me also taste this nectar. He gave me a little bit of the drink. And, repeated the same the following day. Just then my mother saw my grand father serving me liquor. She was furious. She refused to serve dinner to me and my grandfather. I screamed, demanding why she excluded me from dinner. Just then my father intervened and asked my mother what the matter was. She gave him a detailed explanation, justifying her action.

At this, my father started abusing my mother, asking how she dared to check his father and son. He ordered her to serve food to my grandfather. Thereafter, my grand-father started avoiding me, as he felt guilty. Gradually, he gave up drinking. One day, he pleaded with my mother to forget the past and forgive him. He said he had stopped drinking and that she ought not to worry about her son. It was for first time that I saw tears in my grandfathers eyes. When my father got to know about this, he rebuked my grandfather saying, Why did you have to apologize to my wife? If you act in this manner, she will start controlling us.

My grandfather replied, Look son, this has nothing to do with you or me. This concerns our innocent child. That is why you have to be aware of this. But my father said he disagreed with his advice. He said he knew how to manage his family.

Written by Bhagat,

Edited by Sister Mariola

To be continued