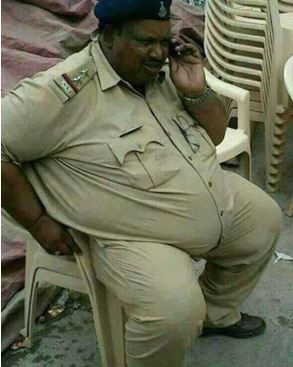

The report by the Director General of Police (DGP), Mr. K. S. Balasubramanian, in the southern state of Kerala to the government, that most of the police officers of the rank of Sub-Inspector of Police are corrupt, inept to discharge their duties and are clinically lazy, speaks volumes about the capacity of the state’s police to serve the people. So far, similar claims were sidelined as mere allegations made by the civil society. The public perception that police officers are criminals in uniform was dismissed as unverified and gross misrepresentation of facts. Now that the head of the police in a state has come to the same conclusion implies that the accusations so far made by the civil society and the public perception, were not mere assumptions, but hard fact.

The report by the Director General of Police (DGP), Mr. K. S. Balasubramanian, in the southern state of Kerala to the government, that most of the police officers of the rank of Sub-Inspector of Police are corrupt, inept to discharge their duties and are clinically lazy, speaks volumes about the capacity of the state’s police to serve the people. So far, similar claims were sidelined as mere allegations made by the civil society. The public perception that police officers are criminals in uniform was dismissed as unverified and gross misrepresentation of facts. Now that the head of the police in a state has come to the same conclusion implies that the accusations so far made by the civil society and the public perception, were not mere assumptions, but hard fact.

The report filed by the chief of police in Kerala, squarely applies to the rest of the country, though similar revealing and honest attempts are absent in rest of India. Given the total strength of police officers in India is 1,585,353 the number of police officers that are unfit to serve the country must be a disturbing news to any responsible government.

That law-enforcement officers in India are grossly unfit to serve is not news. What is shocking however is the neglectful approach that the Union Government as well as the state governments have taken so far on such a serious issue.

The former Home Minster of Kerala state, Mr. Kodiyeri Balakrishnan, once said that corruption among police constables in the state is exceptionally high and that it is an issue to be immediately addressed. He said so, during the graduation ceremony of police constables in Kerala. Subsequent to this, the former DGP, Mr. Jacob Punnose, filed an affidavit in the state high court that 605 police officers are facing inquiries against alleged crimes they have committed. The charges include that of corruption, murder, rape and also torture and deaths in custody. Senior officers like the Additional Director General of Police, Mr. S Pulikessi; Inspector General, Mr. Tomin J Thachankary; and Deputy Inspector General, Mr. S. Sreejith are also included in this infamous list.

In jurisdictions where law-enforcement agencies are considered vital institutions that are foundational to a mature democratic society, abrasions of law-enforcement officers are not tolerated. Discipline and adherence to the rule of law, in every aspect of an officer’s private and public life are monitored and corrective actions, wherever possible, made immediately. For instance, in Hong Kong, police officers have strict limitations concerning even private debt an officer could incur. If an officer is found to have accumulated private debts, which are beyond an officer’s capacity to repay, there are procedures in place that could even end up in an officer losing his or her job. Concerning allegations of indiscipline that have resulted in charges of crime, the officer is immediately placed off duty, the crimes investigated and the officer is prosecuted without delay.

Such hard and fast positions are drawn-up for officers to strictly adhere, due to the recognition governments give to the fundamental fact that a law-enforcement officer is the first in line to defend the rights and entitlements of a citizen. Police reforms that have taken place in jurisdictions where law-enforcement officers are meticulously expected to follow operational as well as legal mandates, that considerably contributed to stamping out corruption in these jurisdictions, have also improved the morale, capacity and the preparedness of the law-enforcement agencies to deal with emergencies, including prevention of crime. The Danish police is often voted by the general public in that country as one of the best civil service institutions in Denmark.

On the contrary, in countries like India, the government intentionally keeps law-enforcement agencies as a corrupt, inept and deeply demoralised institution. This is because those forming governments prefer a demoralised law-enforcement agency that is incapable and unwilling to discharge its duties as expected in a democracy, since that alone is the guaranteed process by which the privileged in countries like India could hold on to their priorities, that are often based also on corruption and crimes.

Unfortunately in India, so far, the subject of police reforms has taken a back seat, even within the police force. Due to lack of internal support and isolation, efforts like those taken by Mr. Prakash Singh finds minimal resonance within the force, and is ignored and waylaid by immoral and criminal forces operating within the establishment.

It is such appalling circumstances that leads to situations like what that has been explained with ample proof in the DGP, Mr. K. S. Balasubramanian’s report to the government. It is the political patronage that corruption receives across India that allows dubious characters that the former DGP, Mr. Jacob Punnose, has named in his affidavit to the court, to continue in service. It is the absence of interest by the larger Indian civil society to address this foundational problem of institution development that maintains the country as an underperforming democracy.

For further information: In Hong Kong, Bijo Francis, india@ahrc.asia, Telephone: +852 26986339