More than 60 convicts have been hung in Pakistan since December 2014. This number is now set to rise, with the military playing its role in executing people. The military junta that has surreptitiously imposed itself upon the pillars of the state, has handed down the death penalty to six convicts over charges of terrorism and heinous crime on April 2, 2015. Blind to the fact that previous military courts and ongoing military operations in Waziristan and other places have failed (AHRC-STM-217-2014) to curb violence and terror, the government has now decided that military courts trying civilians are the answer.

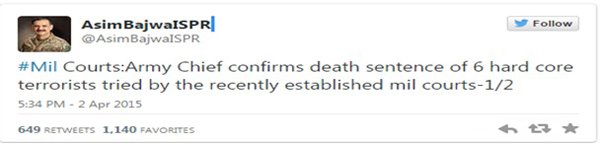

The present military courts were established after making an amendment in the constitution, and the Pakistan Army (Amendment) Act, 2015 provides that the military shall now have the jurisdiction to court-martial militants who are “claiming or are known to belong to any terrorist group or organization using the name of religion or a sect”. While the constitutional amendment has allowed the military to take over the function of the judiciary legally, what is the moral basis for military generals with no training in law, to try civilians and sentence them to death? The arbitrary and opaque way in which the death sentence was pronounced to six convicts and life imprisonment to one on April 2 speaks volumes about the fairness and transparency of their trial. The first names and fate of the convicts were only made known via Twitter by the director general of the military’s media wing, Major General Asim Saleem Bajwa.

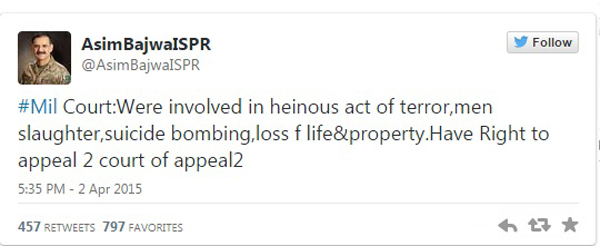

No judgment was released to the media, nor was the description of charges presented; Major General Asim Bajwa only vaguely mentioned the charges in his tweet. In fact, the tweet indicates the whims and will of the army, and paints a grim picture of the state of rule of law in Pakistan.

No judgment was released to the media, nor was the description of charges presented; Major General Asim Bajwa only vaguely mentioned the charges in his tweet. In fact, the tweet indicates the whims and will of the army, and paints a grim picture of the state of rule of law in Pakistan.

According to Dawn news, those awarded death sentences include Noor Saeed, Haider Ali, Murad Khan, Inayatullah, Israr uddin and Qari Zahir, while one Abbas was sentenced to life imprisonment. No other details were given, with the military observing a strict media blackout. This casts a heavy shadow of doubt on the credibility and neutrality of these courts and their proceedings. The summary trial of these seven convicts hardly lasted for a few weeks; how can charges as serious as terrorism and militancy be proved against an individual within the span of such a short time? It is contrary to the norms of justice and the requirements of the Evidence Act (Qanun-e-Shahadat Ordinance, 1984), which these military courts are required to follow, as provided in section 112 of the Pakistan Army Act 1952:

- Rules of evidence to be the same as in Criminal Court.‑Subject to the provisions of this Act, the rules of evidence in proceedings before Courts martial shall be the same as those which are followed in criminal Courts.

Section 113 of the Army Act provides no avenue of appeal:

- Bar of appeals.‑ No remedy shall lie against any decision of a Court martial save as provided in this Act, and for the removal of doubt it is hereby declared that no appeal or application shall lie in respect of any proceeding or decision of a Court martial to any Court exercising any jurisdiction whatever.

It is thus clear that if the convicts are tried and convicted under the Army Act 1952, they have no right of appeal, contrary to General Bajwa’s tweet. His statement can be seen as mere eyewash to appease the public, civil rights activists, jurists and all those staunchly opposing military courts. Established constitutional principles dictate that military tribunals be subordinate to the civilian appellate court and not vice versa; the right to appeal should be vested with the civilian judge.

The legal lacunas that will continue to arise as the military courts hand down more sentences will only complicate matters for defendants who are assumed to be guilty until proven innocent. The right to defense as enshrined in article 10 of Pakistan’s Constitution is not provided to the accused under the Army Act. The only defense plea that a person so tried can take is that of lunacy, as provided under section 130. The appellant authority as provided under section 128 of the act, vests with an officer not below the rank of Brigadier, who may decide the appeal upon merits, “but not on any merely technical grounds”. How can an officer with no legal training decide which matter is technical and which merit? Ultimately, the defendant is left high and dry in trying to prove his innocence.

Furthermore, the proscribed limitation period is three years as provided under the Army Act:

- Period of limitation for trial.‑(1) No trial by Court martial of any person subject to this Act for any offence, other than an offence of desertion or fraudulent enrolment or any of the offences mentioned in section 31, shall be commenced after the expiration of three years from the date of such offence, and no such trial for an offence of desertion, other than desertion on active service or of fraudulent enrolment shall be commenced if the person in question, not being an officer, has subsequently to the commission of the offence, served continuously in an exemplary manner for not less than three years with any portion of the Pakistan regular forces.

According to the Tribune newspaper, the cases of around 3,000 suspected ‘jet black terrorists’(a laughable term not elaborated by the authorities) arrested during the military operations in Swat, South and North Waziristan, and some 300-400 terror suspects being tried at anti-terrorism courts in the provinces, will be sent to the military courts. Many of these suspects committed their crimes more than three years ago; the law of estoppels thus comes into force and the military court cannot try them, giving rise to another legal lacuna.

Instead of developing the country’s criminal justice infrastructure and the most important functionary of the state, the government has outsourced the entire judicial process to the military. This is the third time that military courts have been established citing unusual circumstances; however, this is the first time that military courts were established through a constitutional amendment to silence any dissent from the Supreme Court.

History has shown that not only do military courts fail to curb unrest and militancy, but in fact they further stoke the fire of vengeance amongst the masses. The military justice system cannot handle the intricacies of modern day warfare and militants trained in Islamic fundamentalism. The war of ideology cannot be won forcefully. Rather, a complete overhaul of the judicial system is required. Military courts were cited as a short term necessary evil by their proponents; as they hand down their sentences however, one is further convinced of their arbitrariness. The government of Pakistan must immediately dissolve all such courts and try all suspects under the Anti Terrorist Courts so that justice is served. There is a reason that the military and police are separate institutions: one fights the enemies of the state, and the other serves and protects the people. When the military becomes both, the people tend to become the enemies of the state.