PAKISTAN: Labour Day meaningless for country’s working class

Labour Day in Pakistan is oxymoronic, because the day is just another holiday for the nation’s better off population, while the labour class toils under the blazing sun. Perhaps on no other day does the class difference between the haves and have nots manifest itself as clearly as it does on this day. Throughout the world, the day is marked to commemorate the struggle of the working class; in Pakistan however, that class is kept deliberately unaware of its rights. When the ruling elite become an integral part of the state, the state becomes the exploiter.

Pakistan ratified the International Labour Organization (ILO) Labour Inspection Convention, 1947 (No. 81) in 1953. Under this Convention, the government is bound to ensure that employers and workers are educated and informed on their legal rights and obligations concerning all aspects of labour protection and labour laws; advised on compliance with the requirements of the law; and necessary provisions are made to enable inspectors to report to superiors on problems and defects that are not covered by laws and regulations. The government has not ratified ILO Convention 155 on Occupational Safety and Health and Convention 187 of the promotional framework for Occupational Safety and Health.

Labour legislation

By virtue of the 18th constitutional amendment in 2010, the federal government devolved its power of labour legislation to the provinces. Unfortunately, the job of according provincial status to all labour laws, which was to be achieved in June 2011, remains incomplete. This has resulted in ambiguity in the application of laws in disputes. As of 2015, there are 32 labour related laws operative in Pakistan, including the Mines Act 1923, Employee old age benefit act 1976, Protection Of Women Against Harassment Act 2010, Industrial Relations Act 2012, Merchant Shipping Act 2001, Employment Of Children Act 1991, Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act 1992, and Factories Act 1934. Labour laws are the enactment of constitutional provisions that enumerate labour rights, such as Articles 1, 17, 18, 25 and 37(e). Despite a plethora of labour laws, the labour class is denied their right to safe working environments and better pay. Unions are often discouraged and their demands are curbed using force.

Recently, the workers and staff of Pakistan International Airlines went on strike against the privatization of the national carrier. Their peaceful assembly was interrupted when the Rangers were called in to disperse the crowd, and two senior employees lost their lives in the resultant indiscriminate firing.

Occupational and safety hazards

The legislation in Pakistan on Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) lacks in many ways. The Factories Act 1934 for instance, is not applicable to the enterprises employing less than ten workers. It does not give coverage to the workers in the agriculture sector, informal/house-based and seasonal workers. The majority of the workforce in Pakistan is illiterate and not trained in occupational safety and health.

The mine workers in Pakistan work under some of the worst conditions, worse than the conditions existing 500 years ago. Though the Mines Act 1923 specifically spells out the provisions for health and safety and the responsibilities and duties of inspectors, owners, agents, managers and state officials, yet the officials and workers are unaware of the mandatory safety precautions.

The Hazardous Occupational Rule 1978 is also outdated and unable to manage the complexities associated with existing OSH. The main reason for the lack of implementation of the OSH laws is the collusion of state officials with the owners affiliated with the political elite who cut cost of production at the cost of the workers’ life and health. There is a need for the government to formulate comprehensive rules and regulations to improve OSH awareness and surveillance, as well as reporting on occupational injuries so as to minimize the risk of injuries.

Bonded labour

Ranked third in the world slavery index, there are an estimated 2,058,200 people in modern slavery in Pakistan, equivalent to 1.13% of the entire population. Weak rule of law, widespread corruption and poverty reinforce political, social, and economic structures of modern slavery in Pakistan. Bonded labour is most common in the brick kiln sector, with the majority of kilns in Punjab and Sindh provinces. The government has a limited response to modern slavery, with largely basic victim support services, a limited criminal justice framework, limited coordination or collaboration mechanisms, and few protections for those vulnerable to modern slavery.

By virtue of Darshan Mashih vs. State (1990) the Supreme Court banned bonded labour as unconstitutional. Subsequently, the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1992 was promulgated and enacted. Despite the enactment, the law was not implemented in earnest. The brick kiln workers were not made aware that they didn’t have to break their backs to pay off old debts, magistrates were not informed of their responsibilities and members proposed to be a part of these vigilance committees were not cognizant of their roles.

Child labour

UNICEF defines child labour as work performed by children below the age of 18. Pakistan today has the world’s third largest children’s workforce according to the ILO, while the trend is in decline throughout the world. ILO has put the number of child labourers at 12 million children employees in several hazardous industrial works such as coal, brick kiln, leather tanning and carpet weaving. In December 2014, the U.S. Department of Labour’s List of Goods Produced by Child Labour or Forced Labour reported nine goods of which six are produced in Pakistan.

Pakistan has passed the Employment of Children Act 1991 in an attempt to limit child labour, but the law is universally ignored.

Factory workers

11 September 2012 will remain etched in the collective memory of Pakistan. On that day 259 labourers were burned alive inside a garment factory, Ali Enterprises. The incident is unprecedented in the industrial history of Pakistan, and was termed a 9/11 for the labouring class of Pakistan. In a detailed report, the New York Times stated that two inspectors visited the factory to examine working conditions, and gave it a prestigious SA8000 certification; meaning it had met international standards in nine areas, including health and safety, child labour and minimum wages. Less than a month later, a fire broke out in the factory premises, killing some 300 workers who were trapped behind the locked exit doors.

Despite a lapse of three years, the heirs of the victims have not received any compensation from the state or the factory owners. The Joint Investigation Team found the incident to be a result of arson, thus giving a new twist to the ensuing legal battle. The owners of the factory took it as an opportunity to absolve themselves of the responsibility, leaving the matter of compensation in doldrums.

Article 37 of the Constitution guarantees the right to secure and humane working conditions, while the situation of occupational health and safety in the country is fast deteriorating. The concerned laws too are obsolete and do not conform to international practices.

Minimum wages

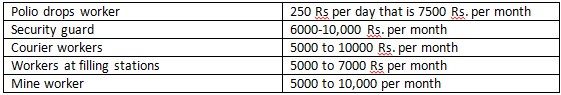

The exploitation of Pakistani workers by most industries, factories and other business organizations is rampant due to a lack of check and balance mechanism on minimum wages by the government. There seems to be no law in the country to curb the exploiters and violators. On the face of it, the provincial governments of Punjab and Sindh have raised the minimum wage from Rs. 12,000 to Rs. 13,000 per month for unskilled workers. Balochistan province has also raised its minimum wage from Rs. 9,000 to Rs.13, 000 per month. While Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has decided to fix its minimum wage at Rs.15, 000 per month, the ground realities speak otherwise. According to the ILO, the wages of workers are as follows:

The state of the pensioners is no different either. Through a 2005 amendment in the Employees’ Old-Age Benefits Act, 1976, monthly contributions payable by the respective employees and employers were linked to the wage under the Minimum Wages for Unskilled Workers Ordinance, 1969. However, despite the fact that the minimum wage was increased from Rs. 8,000 to Rs.10,000 per month effective from 1 July 2013, the Employee Benefit contributions are still paid at Rs. 8,000 due in part to the difference in minimum wage in the provinces. Consequently, the meager pension of Rs. 3,600 per month has not been increased for 354,632 pensioners in Pakistan.

The labor and working class in Pakistan has silently suffered the vicious cycle of poverty brought in by economic meltdown, forcing laborers into the worst forms of servitude and slavery. The state is constitutionally obligated to protect the beleaguered laborers and safeguard their rights, but the state does little more than pay lip service to the cause. Merely enacting laws will not serve the purpose; the implementation of labor laws is the responsibility of the state and must be ensured at all cost. It is about time that the state plays its role in ensuring the social and economic well being of the laborers and fulfills its constitutional and international obligations.