BURMA: Speaker of legislature puts state sovereignty ahead of torture elimination

On 21 March 2013 a member of the national legislature in Burma introduced a motion calling for the country to join the United Nations Convention against Torture. In his motion, Dr Aung Moe Nyo, member of the National League for Democracy for Pwintbyu, Magway Region, argued that as the country is now developing and democratising in accordance with international standards it would be appropriate to join the convention. He also pointed out that five other member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, being Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Philippines and Thailand, had all joined the treaty, implying that it would also be consistent with practice in the region for Burma to do the same.

On 21 March 2013 a member of the national legislature in Burma introduced a motion calling for the country to join the United Nations Convention against Torture. In his motion, Dr Aung Moe Nyo, member of the National League for Democracy for Pwintbyu, Magway Region, argued that as the country is now developing and democratising in accordance with international standards it would be appropriate to join the convention. He also pointed out that five other member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, being Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Philippines and Thailand, had all joined the treaty, implying that it would also be consistent with practice in the region for Burma to do the same.

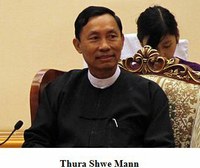

The motion ought to have been a moment for some small celebration, another indication that Burma is making firm progress away from its repressive, militarised past and towards a new form of government in which the use of torture is eschewed, and over time, eliminated. Indeed, that it obtained tacit or explicit support from other persons assembled–including a judge of the Supreme Court–is significant. However, at the end of the debate, the speaker of the house, Thura Shwe Mann, made a number of observations about the motion that speak volumes of the deeply conservative, persistently anti-human rights mentality of the former military officers still holding key positions throughout Burma’s government.

First, Shwe Mann noted that the home affairs ministry–which remains under control of a uniformed army officer and which is responsible for management of the police force, prisons, and Bureau of Special Investigation, agencies responsible for widespread and routine use of torture as recounted by the Asian Human Rights Commission in numerous appeals and other interventions over the last decade–had indicated in response to the motion that already personnel are obligated to act lawfully and that those who do not need to be given exemplary punishment. The implication here is that the necessary measures are already in place to deal with torturers. This kind of spurious reasoning is typically heard among officials in countries resistant to joining the convention: that they already have laws and measures in place to punish wrongdoers, and that additional measures on torture are unnecessary. Not only do such arguments ignore the empirical fact that if torture is widespread and routinized, as it is in Burma, then clearly such measures are inadequate, but also they ignore the well-established propositions of international law that the crime of torture is of an exceptional quality, and one that deserves exceptional measures. Therefore, this first point contains nothing to prohibit or inhibit Burma from joining the convention.

Second, Shwe Mann pointed out that although five ASEAN countries had joined the treaty, it was after all only five, and that anyhow, countries signed treaties not necessarily for altruistic reasons but because there is something in it for them. This profoundly cynical view might have some veracity, but it is alarming to hear the speaker of the national legislature openly stating that, in effect, the norms of international law matter not because countries do or do not sign up where they have strategic incentives. This viewpoint is cut straight out of the handbook on international relations used by the military for the last couple of decades, in which the key rules were to sign nothing, and deny everything. With this sort of mentality continuing to prevail among senior figures of government in Burma, it is hard to see how the country will make the expected progress in its dealings with the international community, at least on human rights issues.

Third, and perhaps most alarmingly, Shwe Mann got to the crux of the matter when he said that state sovereignty and human rights are uncomfortable together, and that when considering such matters regard had to be had for the interests of the state and citizens. Again, the speaker here is at his most dangerous, inasmuch as his statements contain some elements of truth. Questions of human rights and state sovereignty do sometimes come into conflict, which is precisely why the prohibition on torture with which the motion was concerned is a universal principle and a jus cogens norm, meaning that it is one from which no state can derogate on the ground of sovereignty. In other words, where torture is at issue, human rights trump sovereignty. No room for debate exists on this question, except in countries like Burma where the perpetrators of torture enjoy impunity for their actions with the tacit endorsement of men like Shwe Mann. Indeed, the only way that the state and its citizens could fail to be advantaged by their state joining the Convention against Torture would be if the state views its interests as hostile to those of the citizens, and is obligated to resort to torture to maintain its superior position against those of the citizenry–precisely the situation that Dr Aung Moe Nyo has sought to address by bringing forward his motion.

The speaker concluded the debate by instructing responsible agencies to take the matter up for implementation of their own accord. Although this instruction can be read as an endorsement of measures to join the treaty, it could also function as a “do nothing” clause, since the matter could easily rest with any of the concerned agencies without prompt action, for any amount of time. The people of Burma cannot afford to wait. Every week, the AHRC receives reports, complaints and detailed accounts of the continued use of torture in police stations, council offices, military camps and other facilities around the country, oftentimes resulting in death. Only a few victims or their families attempt to obtain redress, since the obstacles to the making and hearing of complaints are enormous, and the risks also considerable. These citizens of Burma need ratification of the convention.

To this end, the Asian Human Rights Commission urges members of the legislature in Burma to join with Dr Aung Moe Nyo and continue to bring forward motions on the question of torture, raising specific cases, and challenging the speaker’s ideas about international law and human rights, for as long as necessary to force a swift change in policy. It urges members of the public to join with concerned legislators in making calls for the UN Convention against Torture to be ratified, and by raising the profile of torture as an ongoing human rights issue, offering support to victims and their families. The print media, which has perhaps benefited the most from political and social changes over the last couple of years, should be especially involved, using its voice to carry a message about the need for change. Proliferating civil society groups and democratic political parties should make plans to prepare for the International Day in Support of Victims of Torture on June 26.

Lastly, to the international community, the AHRC calls on governments around the world–including those of the five ASEAN countries that have joined the convention–to urge that the government of Burma join the Convention against Torture and give effect to it at home as soon as possible. And if the speaker’s attitude is that carrots and sticks are required to get countries to sign on to international laws, then in bilateral and multilateral relations all governments concerned with the elimination of torture ought to dangle carrots and wave sticks: tie offers of assistance to ratification of the convention; make plain that the contents of international law matter, and that the elimination of torture is not a matter of striking a balance between sovereignty and human rights, but a global imperative that cannot be so easily swept aside after all.