PHILIPPINES: The importance of arresting retired general Jovito Palparan Jr.

In the streets of Metro Manila, it is common to see photographs or posters of missing persons posted on walls and electricity poles, with details of the missing person and how to contact the relatives looking for them. These families have taken it upon themselves to look for their loved ones, in the absence of any help from the government.

In the streets of Metro Manila, it is common to see photographs or posters of missing persons posted on walls and electricity poles, with details of the missing person and how to contact the relatives looking for them. These families have taken it upon themselves to look for their loved ones, in the absence of any help from the government.

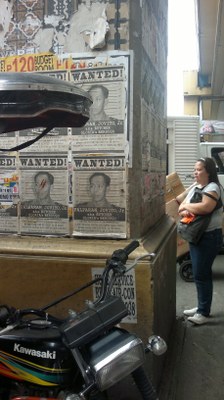

What is not common however, is the poster of Jovito Palparan Jr., a retired military general, also posted widely on public walls in Manila. He is not a missing person, but a person who went into hiding after the court issued arrest orders against him, to answer allegations of his and his men’s involvement in the disappearance of two activists, Sherlyn Cadapan and Karen Empeno in 2006 (See Story No. 86 for details). The inability of the government to arrest him is not surprising; in fact, him being actually arrested would be more of a surprise. (photo: Jovito Palparan’s wanted poster in streets of Manila)

Failure to arrest persons subject to court arrest orders is not unique to Palparan. The failure or inability to arrest is unfortunately a norm more than an exception throughout the Philippines. Even ordinary criminals or escapees from jail can in fact roam freely. Unless they make trouble again, or they apply for employment requiring police clearance, they are not likely to be arrested. Under such circumstances, how can society expect Palparan to be arrested?

Firstly, Palparan is not an ordinary man. Before he retired from the military, he commanded military units and was assigned to various different regions. His military accomplishments–regardless of whether they conform to the articles of war and human rights norms, which the military establishment claim to adhere to–are publicly endorsed and recognized by his former commander-in-chief, former president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo.

Secondly, Palparan is well known to the government. All of his personal and military records are well documented by the Armed Forces, not only as a military officer, but also as a civil servant subject to civil service laws. In performing his duty in the military, he is subject to both administrative and criminal proceedings. As a known military general well endorsed publicly by the former president, it is hard to imagine that the government, particularly the military establishment, does not know where Palparan is.

Thirdly, Palparan’s military career and achievements was strongly endorsed during Arroyo’s presidency. In other words, Arroyo consented to Palparan’s actions and his rhetoric justifying the fight against counter-insurgency and protecting the rights of only those people he considered as ‘humans’. Now that Arroyo herself is under hospital arrest and being prosecuted for election fraud however, where does Palparan’s support lie?

Despite the change in leadership and government knowledge regarding Palparan, there are today posters put up in search for him. This is a clear indicator that the assumption that any police or military officer who committed violations during Arroyo’s time could be held accountable once the leadership is changed, is deeply flawed. The dominant thinking that change of leadership is prerequisite to accountability for gross human rights violations has been flawed for many years; this did not happen in the present Aquino term, nor did it occur in the regime of Corazon Aquino after Marcos, or in Gloria Arroyo’s regime after Estrada.

Rather, it is clear that those accused of crimes, regardless of whether they are government civil servants, policemen or military officers, have developed sophisticated methods of escaping from accountability. At the same time, the relatives and victims of human rights violations are also developing creative means to deal with this absence of accountability; the distribution of Palparan’s poster being one such method.

Escaping arrest for instance, is not a special skill unique to Palparan. Needless to say, the current Philippine Senator Panfilo Lacson himself had gone into hiding and absconded from his responsibility as a lawmaker to evade the very jurisdiction of law he was mandated by the people to uphold. In his defence, he also claimed innocence of the murder charges against him for the assassination of the former publicist of President Estrada. After the court dismissed the charges, he surfaced bragging about his exploits while in hiding.

Like Palparan, Lacson is also a ‘decorated police officer.’ He had been accused for committing torture and human rights violations during his career as a police officer before joining the Senate. The difference is that the charges on Lacson were dismissed, while Palparan’s charges had just begun. In the Philippines, jurisprudence says that flight is an indication of guilt; Lacson can now afford to show up in public, while Palparan cannot. However, there is one thing that these individuals have in common: the capacity to hide from the law using their connections with the police and military.

The spread of posters of Palparan in the streets of Manila, initiated by Karapatan and the families of the victims who took responsibility in asking to locate him, demonstrates an utter state of impunity that continues to thrive in the country. In the case of Palparan and his men involved in forced disappearance, even the Department of Justice and its attached special investigation unit, the National Bureau of Investigation, have openly admitted being unable to arrest them, despite their resources and intelligence network all over the country. While the government may be willing to arrest Palparan, it seems its willingness does not match its ability.

The failure and inability of the government to arrest Palparan should therefore be examined thoroughly by the country’s justice institutions to address unresolved cases and the ongoing impunity of past regimes. The skills and habits to evade accountability developed by the offenders of the law, particularly the security forces expected to uphold the law, must first be learned and understood. No reform can be made possible without this knowledge. This is not only about arresting Palparan or him evading prosecution, but rather narrating the state of justice institutions that exist in the country.