The frenzy of land grabbing in Burma (Myanmar) amid the country’s transition to nominally democratic government shows no signs of abating. Reports of the number of cases and scale of “land confiscation”—a euphemism for theft by government authorities and army-linked cronies—continue to grow. At the same time, conflicts over land have escalated as farmers attempt to regain land taken from them in earlier years.

A consistent feature across these reports is the role that the courts and police have played in support of cronies and military interests. The most recent case in which the regressive and anti-democratic role of the courts and cops was openly on display occurred last week in Pegu (Bago) Region, when a court heard a case against five farmers accused of upsetting public tranquillity for demonstrating publicly over the loss of more than a thousand acres of farmland in 1997, to Infantry Battalion 80, based at Inma, and a crony, U HtainHtain, alias Hla Moe.

The farmers in Thegon Township began protesting publicly in February 2014 after having sent over 60 complaint letters to some 24 government department and agencies, without getting any satisfactory response. In February, four of them—Ko Thant ZinHtet, Daw Win, Daw Nyo and KoPauk Sa—were arrested and charged under section 18 of the Peaceful Assembly and Demonstration Law for protesting without a licence. In the course of making the arrests, police assaulted a number of demonstrators, and two women were hospitalised.

As the Asian Human Rights Commission has written previously, this law does exactly the opposite of what it claims to do: rather than enabling people to gather and express their views freely and democratically, it criminalises people for organising public rallies without having first obtained permission from the authorities, who can approve or deny the holding of such events arbitrarily. Hence, anti-Muslim fanatics get permits to rally, while farmers fighting against the army and army-backed interests do not.

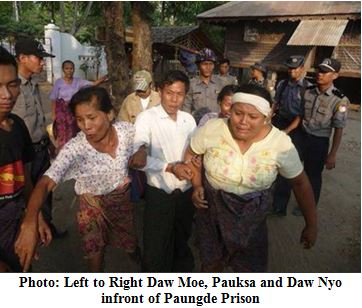

Unbowed, the farmers on April 23 engaged in another act of public protest, this time burning a number of coffins bearing the names of the crony, military and government authorities responsible for denying them return of the stolen farmlands. Thereafter, on May 2 the police lodged another case against five farmers—KoPauk Sa, KoKyaw Thu, Daw Nyo, Daw Mone and Ko Thant ZinHtet—under section 505(b) of the Penal Code, for allegedly upsetting the public tranquility with their coffin-burning ritual. The Thegon Township Court set May 6 as the date for a hearing.

On the date of the hearing, the court ordered PaukSa be taken into custody rather than released on bail. The police took him from the courthouse in handcuffs. At the entrance to the Paungde Jail, an argument broke out between assembled farmers and police as the latter tried to take PaukSa inside, and around 50 police were called to cordon off ten farmers. A police officer also assaulted a journalist present.

The Thegon case, like others of its type, is illustrative of the extent to which the authorities and political and economic interests in Burma continue to operate according to military-arranged networks, embedded over half a century of dictatorial, repressive rule. The police and courts are to this dayalmost exclusively responsive to the demands and needs of the army and cronies with which it has connections. To the extent that farmers and other members of the public succeed in getting back land or obtaining satisfaction in relation to other demands, it is only where and when those established military and business interests acquiesce to them. Where the army or people with whom it has close relations decline to accommodate public demands, farmers like those in Thegon get nothing, and other parts of the state apparatus do nothing.

The networking of military and business interests into the current nominally democratic period is particularly damaging and dangerous not for the cronies or soldiers, who continue to rake in unknown amounts of illicitly obtained gains, or even the cops and courts who are at their beck and call, but for those innovative institutions to which people are looking for redress. These nascent democratic agencies—which include the various committees and commissions established to investigate and secure the return of lands, and also the rule of law committee headed by Aung San SuuKyi—are increasingly being shown up as hollow, meaningless and pathetic bodies.

These committees are among those inundated with complaints of the sort sent by the farmers from Thegon; complaints for which members of the public very rarely receive any reply, and even less often, any evidence of redress. Of course, the committee members are right to complain (privately) that they have neither the authority nor resources to carry out their mandates: they do not. But the farmers in Thegon and thousands of other places around the country from which similar complaints have emanated over the last few years do not get this message. The message they get is that no matter how much they raise their voices through official channels, they get nothing but silence in reply.

Therefore, the only means they have to obtain some kind of response from the state authorities is to take to the streets, and meet with the cops and courts that do the cronies’ bidding. In so doing, they gain confidence in their own abilities to rally and fight for what they believe in, but they also lose confidence in the ability of any of those nominally democratic institutions to do anything for them. Above all, they lose confidence in legal institutions at precisely the time that these agencies ought to be a part of the movement for political and legal reform in Burma, not obstacles to it.