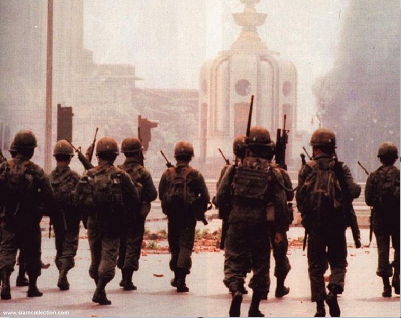

Thailand is a constitutional monarchy, where the king serves as head of state and has traditionally exerted political influence. In May 2014, military and police leaders, taking the name of the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) led by General Prayuth Chan-o-cha, overthrew the interim government led by the Pheu Thai political party. The NCPO replaced the 2007 Constitution with an interim constitution.

The NCPO has maintained control over the security forces and all government institutions since the coup. With regards to the justice system, prior to the coup, the Thai justice system was recognized as independent and the government generally respected it. Since the NCPO overthrew the interim government, declared martial law, issued a series of NCPO orders and announcements and imposed Article 44 of the interim constitution however, both the civilian and military court systems have been affected.

According to Article 44 of the Interim Constitution, General Prayuth Chan-ocha, as the junta leader and Prime Minister, has absolute power to give any order deemed necessary to “strengthen public unity and harmony” or to prevent any act that undermines public peace. As a result, the status of the order issued under the power of Article 44 is equal to an act passed by the legislature.

According to Article 44 of the Interim Constitution, General Prayuth Chan-ocha, as the junta leader and Prime Minister, has absolute power to give any order deemed necessary to “strengthen public unity and harmony” or to prevent any act that undermines public peace. As a result, the status of the order issued under the power of Article 44 is equal to an act passed by the legislature.

This article affects civilian law enforcement directly due to the fact that even though martial law was revoked on 1 April 2015, it was replaced by NCPO Order No. 3/ 2015, which was issued under the authority of Article 44. In practice, the effect is no different from martial law as the order permits the boundless exercise of power and also inserts military officials into the judicial process and provides them with the authority to carry out investigations along with the police. In addition, the order gives authority to military officials to detain individuals for up to seven days. During this 7-day period of detention, detainees do not have the right to meet with a lawyer or contact their relatives, and the military officials further refuse to make the locations of places of detention public.

As a result, many forms of human rights violations have occurred throughout the country. According to Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR), since 22 May 2014 until 30 April 2016, at least 1,006 individuals were summoned to report to authorities for questioning and attitude adjustment, while 130 academic discussions and public forums were prohibited and intervened by the authorities. Moreover, at least 579 individuals were arrested and sized under NCPO Order No. 3/ 2015.

Further, the prosecution of some civilians by military courts for offences stipulated in NCPO Announcements Nos. 37, 38 and 50 is of grave concern. Although the Thai government processed civilians in military courts due to the charge under the Anti-Communist Activities Act B.E.2495 (1952) and during the political conflict on 6 October 1976, the AHRC views the present use of the military judicial system in civilian cases to be graver and more expansive than in the past.

This is due to the fact that under Announcement No. 37/2557 of 25 May 2014, the NCPO made clear its intention to establish military courts to process people accused of certain categories of offences. In particular, it listed offences of lese majeste, offences concerning internal security, and any offences deemed to be contrary to the orders of the NCPO. In Announcement No. 37/2557, it added that persons brought before military courts with cases pending against them from the ordinary criminal courts could have those cases dealt with simultaneously. Moreover, on 30 May 2014, the NCPO issued Announcement No. 50/2557, which placed weapons-related cases within the jurisdiction of the military court, retroactive to 4:30 pm on 22 May 2014.

According to the Judge Advocate General’s Department (JAG), from 22 May 2014 – 30 September 2015, there have been 1,408 civilians tried in the military court including 1,629 alleged offenders/defendants, most commonly for violations of Section 112 of the Thai Criminal Code (lese majeste, defaming or insulting the king, queen, heir-apparent, or regent), failure to comply with an NCPO Order, and violations of the law controlling firearms, ammunition, and explosives.

The AHRC and other rights groups are particularly concerned by the practice of prosecuting civilians in military courts, due to the lack of legal rights. In ordinary criminal courts, defendants have a broad range of legal rights, including access to a lawyer of their choosing, prompt and detailed information of the charges (including no-cost interpretation if needed), and adequate time and facilities to prepare a defence. These are not provided in the law for the establishment of military courts. For example, military courts do not afford civilian defendants rights to a fair and public hearing by a competent, impartial, and independent tribunal. Also, civilians have to seek private counsel from among the limited number of lawyers able and willing to take their cases in military court. In addition, civilians facing trial for offenses allegedly committed from 22 May 2014 to 1 April 2015–the period of martial law–have no right of appeal.

With regard to Internet Law Reform Dialogue (iLaw) and TLHR, there are some particular cases in military courts that should be noted. On 26 June 2015, police arrested “the 14 student activists” from the New Democracy Movement group, who carried out a symbolic action at the Democracy Monument on 25 June 2015. They were charged with violating NCPO Order No. 3/2015 banning gatherings of more than five people and Section 116 of the Thai Criminal Code (sedition).

It is worth noting that the remand hearing of the 14 student activists took place at night. Normally, the Military Court’s office hours are until 16:30, but on that day, the Military Court was open at 22:00 when the inquiry officers handed in the request for the remand. The whole process for the remand hearing finished at 00:30. It was the most late-at-night remand hearing known to have taken place, and according to critics, it reflected the military court’s clear lack of independence and impartiality.

In addition, when an accused person decides to fight the charge in the Military Court, they fall into the trap of delays, as in the case of “Sirapop, Anchan, and Tom Dundee”. Since the announcement has been made in 2014 to authorize the Military Court to have jurisdiction over cases against civilians, the military court has scheduled the hearings in a drawn-out, staggered fashion. During some hearings, the prosecution witnesses were simply absent without informing anyone in advance. Therefore until the end of 2015, none of the trials in the cases in which the accused has decided to fight the charge have been completed.

Furthermore, the military court also meted out hefty punishment in the case against “Thiansutham”. He was found guilty by the military court on five counts from posting five Facebook messages, and sentenced to altogether 50 years, prior to a reduction to 25 years. “Pongsak” was found guilty on six counts by the military court from posting six Facebook messages and was sentenced to 60 years prior to the reduction to 30 years, and “Sasiwimon” was found guilty on seven courts by the Chiang Mai military court and was sentenced to 56 years prior to reduction to 28 years.

It is therefore clear that the military courts do not accord the same rights as Thailand’s civilian courts, while also violating internationally protected fair trial rights, especially rights to fair and public hearing by a competent, impartial, and independent tribunal, and the rights to legal representation and appeal. The AHRC thus calls for the NCPO to revoke Article 44 of the Interim Constitution and the NCPO orders and announcements that place civilians in military courts, and end all forms of violations and harassment to ordinary people.