INDIA: Can the Supreme Court end the reign of criminals in politics?

The judgment of the Supreme Court of India delivered on 10 July 2013 in Civil Writ Petitions 490 and 231 of 2005, declaring Subsection (4) of Section 8 of the Representation of People’s Act, 1951 as ultra vires the constitution, is a watershed event. The Court on the same day dismissed two other Civil Appeals, 3040 and 3041 of 2004, holding that if persons held in lawful custody other than preventive detention cannot vote in an election, such persons are also not allowed to contest elections. The Court’s interpretation of the 1951 law vis a vis the constitutional scheme has the potential to stymie criminals perpetually contesting elections in the country.

The judgment of the Supreme Court of India delivered on 10 July 2013 in Civil Writ Petitions 490 and 231 of 2005, declaring Subsection (4) of Section 8 of the Representation of People’s Act, 1951 as ultra vires the constitution, is a watershed event. The Court on the same day dismissed two other Civil Appeals, 3040 and 3041 of 2004, holding that if persons held in lawful custody other than preventive detention cannot vote in an election, such persons are also not allowed to contest elections. The Court’s interpretation of the 1951 law vis a vis the constitutional scheme has the potential to stymie criminals perpetually contesting elections in the country.

Political parties and a substantial section of the Indian media have expressed concern about the judgments, citing reason that such a blanket prohibition is susceptible to misuse. They allege that persons could be victimised from contesting elections or may lose seats to which they are elected, if their case falls under the remit of the jurisprudence laid down by the court in the four cases cited above.

Deciding on Subsection (4) of Section 8, the Court ruled that the saving clause provided in the 1951 law, allowing a person convicted for an offense to retain his or her seat in the state assembly or in the parliament, “…until three months have elapsed from the date of conviction or, if within that period an appeal or application for revision is brought in respect of the conviction or the sentence, until that appeal or application is disposed of by the court…”, is ultra vires the constitution.

Citing Articles 101 (3) (a) and 193 (3) (e) of the Constitution, the Court ruled that disqualification becomes effective the moment a person is convicted. The only exception to this rule is when a person convicted has filed a revision or appeal in which the sentence and conviction is suspended by a superior court within 90 days.

The Court also ruled that while Subsections 1, 2, and 3 of Section 8 deal with the disqualification of persons from contesting elections on the ground of conviction in criminal cases, the saving clause in Subsection 4 concerning disqualification of elected representatives – which was subsequently incorporated into the 1951 law – as an act of the parliament that exceeds its constitutional remit provided in Articles 102 (1) (e) and 191 (1) (e) of the Constitution.

Concerning Subsection (5) of Section 62 of the 1951 law, the Court said that a person in lawful custody, whether convicted or not of a criminal offense, is not an ‘elector’, since registration of persons in lawful custody is prohibited under 16 (1) (c) of the 1951 law. The Court refrained to apply a different set of principles to ‘disqualified electors’ that may wish to contest an election, ruling instead that if a person is disqualified to be an ‘elector’, the same person cannot contest elections. This means any person in lawful custody cannot contest elections from now on in India.

The Court did not accept the government of India’s argument that this interpretation of the law would cause hardship to persons since the penal code and the criminal procedure could be misused. The Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) is of the opinion that while such an argument speaks volumes about the criminal justice apparatus in India, the remedy for probable misuse of criminal law and procedure is in correcting the defects of the criminal justice process and not in providing excuses so persons convicted of serious offences can continue contesting elections or maintaining seats of power.

The approach tells an old continuing tale of the Government of India letting its criminal justice apparatus decay, making and keeping it as pliable as possible, so criminals in power politics get away with their criminal deeds. Having no policy of adequately reforming the criminal justice system is India’s policy.

That convicted criminals have exploited the omnipresent cracks in India’s criminal justice machinery is not news. At the moment, from statutory declarations made by elected representatives to the Election Commission of India, 162 out of 543 members of the lower house of the Indian parliament, the Lok Sabha, face criminal charges. Mr. Kameshwar Baitha, aged 60 years, against whom there are 35 criminal offences, including murder, registered at various police stations, tops the list. A whopping 1,258 out of 4,032 sitting legislators in the state assemblies have criminal cases against them.

It is obvious that these persons can make the entire criminal justice apparatus work in their favour. All these cases are registered before 2009. And in most cases, the trials have not been completed. For instance, Mr. Harendrakumar Ramchandrad Pathak from Gujarat, a sitting member of parliament, has trials pending against him since 1985. Similarly, Mr. Ahir Hansaraj Gangaram from Maharashtra has 30 criminal cases pending against him, of which the oldest stretches back to 1987. According to records filed by Gangaram, he has been charged with at least one criminal offense of a serious nature every alternate year since 1987. His criminal record with the police began at the age of 30, like Pathak. Both Pathak and Gangaram represent the Bharatiya Janata Party, a political party professing fundamentalist religious policies.

The allegation that the police can be misused against politicians further speaks about criminal investigation in India, which begins and ends with a confession statement, often extracted with the use of brute force.

The police are ill-equipped, understaffed, and grossly undertrained. More than 90 percent of police officers do not know how to undertake a scientific investigation. Arrest precedes investigation, since confession statements are the foundation stone of criminal cases, despite such statements being, by themselves, inadmissible as evidence in a criminal trial. The police as an institution is also deeply corrupt. Today a person who could pay a police officer a bribe could get a case registered against anyone.

The police suffer deep distrust, as an institution as a whole and within the organisation as well. It is routine practice among senior judges in the country to advise new judges to exercise extra caution in criminal cases where the case diary is impeccably built, suggesting that such records are often the products of bribed officers making up a fabricated charge against an individual.

If the country’s politicians are serious in reforming the political landscape in India, their first interests should be in reforming the criminal justice apparatus of the country, beginning with the police. If this happens, no politician will fear that the country’s criminal justice process may be misused to prevent anyone contesting elections. It is in this context that their present lament against judicial intrusion into legislative processes is doing no good to India.

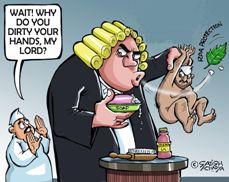

Cartoon provided by: Mr. Sathish Acharya http://cartoonistsatish.blogspot.hk/