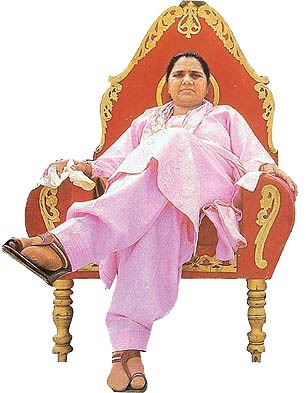

In what appears to be an ‘absolutely normal’ practice in India, the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh state, Ms Mayawati, has declared, that one of her ministers, accused of having raped a girl, is not guilty. The chief minister also declared, that there would be no investigation against the minister.

In what appears to be an ‘absolutely normal’ practice in India, the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh state, Ms Mayawati, has declared, that one of her ministers, accused of having raped a girl, is not guilty. The chief minister also declared, that there would be no investigation against the minister.

The incident of rape of the girl, allegedly by one of Mayawati’s ministers reportedly happened in 2007 in Chitrakoot district. It is reported that the girl had given a statement to a judicial magistrate, in which she has named the minister. However later when the police registered a crime, the name of the minister was omitted. Instead the minister’s personal assistant is accused of raping the girl in 2005.

Indeed there are inconsistencies in the girl’s statements. Yet one could ask a few questions: (1) in the conditions that prevail in India, how can a girl who is allegedly a victim of rape, be expected to give consistent statements? (2) was the girl provided any form of professional counselling before recording her statement?; (3) are there any such functioning government facilities in Uttar Pradesh? (4) more importantly, is it for the chief minister of a state to decide who is guilty of a crime? The legal and commonsense answer to all these questions is an emphatic NO.

Indeed the accusation could be politically motivated and hence a fake case. If it is so it once again speaks about the horrendous state of affairs in the country of how easy it is to misuse the justice system to wreck political vengeance, for which a child is made to make an accusation of rape. Yet in a state like Uttar Pradesh, none of this seems to matter, before Mayawati and during her tenure, dubbed as the ‘golden era’ of the state.

The Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) has information that immediately upon taking charge as the chief minister, Mayawati had directed the state police to discourage registering of cases. The retarded purpose behind this illegal and non-written order is to gerrymander the crime statistics in the state to show that Mayawati’s government has succeeded in controlling crime. But at the same time, Mayawati has used the state police to cull down her political rivals, including those within her own party, which has been lauded by myopic political commentators and the media as “the new chief minister cracking down crime”.

Just as it has happened in the minister’s case referred to above, the curse of the Indian police is political interference. A chief minister has no legal authority to prevent the investigation of a crime. The constitutional privilege to the members of the state assembly does not apply to an accused in a rape case. Uttar Pradesh however can be an exception to even the constitution.

In any country that claims to be respecting the rule of law, when a child accuses a person of having raped her, the minimum expectation is that the complaint will lead to an investigation and if the investigation reveals a crime, a prosecution would follow. However in India, just as Mayawati has put her foot down in this case, to declare her crony ‘not guilty’ without investigation or prosecution, crime control is left to the whims of the politicians and their cronies who consider themselves to be above the law or law unto themselves.

In that what Mayawati did is no exceptional act, but fits the norms and standards of what is uniquely conceived as ‘justice’ in India. Unacceptable it might be in jurisdictions where the rule of law is the norm. But India is not such place, and Uttar Pradesh is in India.