Women News Network

March 21, 2010

Correspondent, Shuriah Niazi — Women News Network — WNN

Chhattisgarh, India: Mita Bai, 34, will never forget the morning of May 6, 2005. It was 8 a.m. in the morning when a group of three men and six women came to her house with their allegations, branding her as, “a witch.” As an attack against her broke out, she cried out for help, but no one heard or heeded her pleas. Instead, she was dragged from her home, stripped of all her clothing, and nearly hung from a tree.

What was her crime? She was accused of bringing misfortune to others in the village as a practitioner of “Dayan Pratha,” known in rural India as the practice of witchcraft.

What was her crime? She was accused of bringing misfortune to others in the village as a practitioner of “Dayan Pratha,” known in rural India as the practice of witchcraft.

Kerva village in Chhattisgarh is near a vast, deep forest. The road to the village is so remote and difficult to reach that there are no buses; only a slow four-wheel drive vehicle can negotiate the terrain. With the nearest police station 40 kilometers away, police rarely venture into to the village.

After this incident, police visits have increased dramatically, with arrest warrants for the six women and three men. Four of the wanted individuals are still in hiding.

In India today witchcraft allegation, persecution and violence is not diminishing. “Over the last fifteen years, an estimated 2,500 Indian women have been killed because they were ‘witches’.” – Rebecca Vernon, Editor, Cornell University International Law Journal

“Witch hunts are most common among poor rural communities with little access to education and health services, and longstanding beliefs in witchcraft,” Vernon continued. “When an individual gets sick or harm befalls the community, the blame falls not upon a virus or crop disease, but upon an alleged witch.”

A Heartbreaking Case

Mita Bai made her way to the police station on the day she was accused of witchcraft, begging for protection. She told the police how the group came to her house demanding she leave the village and how they physically dragged her out of her home. “They beat me up with sticks and rods and tried to hang me. When I overpowered them, they hounded me out of the village,” Mita recalled. She has now taken refuge in a nearby village, weeping continually in a way that is truly heartbreaking for anyone who witnesses it.

While Mita suffers in exile, the turmoil has also caused villagers to express their own anger. According to them, they were only punishing Mita Bai for acts of witchcraft she had performed. “She is here to kill us,” said Manju, a 24 year old member of the community.

Witchcraft in India is still part of the rural culture of India. Violence against women who are accused of being witches is generally present and pervasive. This violence can be so severe and dangerous, it can result in the death of women who are accused.

“Greed for property is one motivation behind witch-killings.” – Dinesh Mishra, Head of advocacy group, Andra Shraddha Nirmulan Samiti “The struggle for gender equality is also a factor in the persecutions, as are poverty and economic inequalities,” said Dinesh Mishra, who heads Andra Shraddha Nirmulan Samiti, a non-governmental organization based in Raipur in Chhattisgarh state, which fights against the harassment of women in the region.

Society, Religion and Witchcraft in India

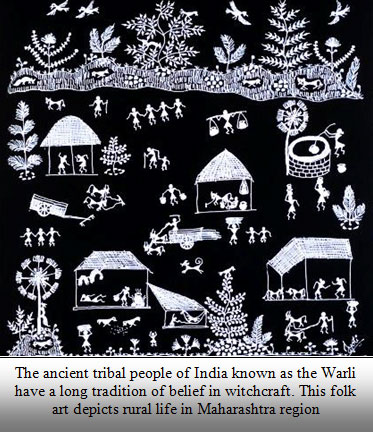

Oppression of women as “witches” can be traced back to the first social communities in India. Local women, who fulfilled the role of healer and counselor, were feared when they became too powerful for the male leadership to control. As women gained power in their community, excuses were found to “bring them down to their place.” “The practice (of persecution) is mostly prevalent in tribal belts,” Dinesh Mishra explained further. “The villagers blame anything they don’t understand on (the most ancient Hindu customs of) tantra.”

The Hindu religion of India called Sanathana Dharma (The Universal Religion) has many beliefs and rituals. Numerous ancient practices have rituals that can be interpreted and viewed as witchcraft or paganism. Practices include the worship of nature in its various forms, as the qualities of nature are embodied as numerous gods and goddesses.

Those who follow the most ancient of the customs can be misunderstood and summarily accused. This can cause a conflict for the very pious, as the devotion of women to ancient traditions can be mistaken for “witchcraft.”

Today ostracism and severe violence against women accused of witchcraft is occurring at an alarming rate in the village regions of Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar, along with numerous other rural regions in India.

“Poor, low-caste women are easy targets for naming/branding (as a witch).” – Kanchan Mathur, Professor at The Insititute of Development Studies India

“Women who are widowed, infertile, possess ‘ugly’ features or are old, unprotected, poor or socially ostracized are easy targets,” said professor Kanchan Mathur, from the Institute of Development Studies India, in a recent 2009 report.

Accused women are often blamed for any misfortune that befalls their village. Some of the misfortunes that lead to accusations may also include natural disasters, such as droughts, floods, crop loss, illness or, dramatically, the death of a village child.

With such unjust public charges made against her, how could Mita Bai ever return to her own village to lead a normal life?

Once a woman has been accused of witchcraft inside her own society, it is difficult for her to ever escape the stigma. She can suffer severely the rest of her life. On guard at all times, she can be hurt at any time by ongoing public humiliations that range from public beatings, forced hair shavings, and forced acts of physical torture; such as being forced to go naked in public or to perform public acts of humiliation.

Violence against women in this case can escalate into serious actions that can lead to a woman’s death.

Witch Hunting

Witch hunting in India is not an ancient practice that has been left to history. It is currently still widespread in Madhya Pradesh. But it is most prevalent in the tribal-dominated areas of the state. In the districts of Rajgarh, Khargone, Badwani and Jhabua, where accusations of witchcraft are unfortunately common, many older women who are accused cannot defend themselves in any way.

In the tribal villages, the village ‘ojhas’ (known as ‘sorcerers’) boast of their powers to detect a witch but they will only do so “for a price.” For the ojha to declare a woman a witch, villagers simply need to cough up a goat, a bottle of liquor, or any other poultry animal to pay the ojha.

In the tribal villages, the village ‘ojhas’ (known as ‘sorcerers’) boast of their powers to detect a witch but they will only do so “for a price.” For the ojha to declare a woman a witch, villagers simply need to cough up a goat, a bottle of liquor, or any other poultry animal to pay the ojha.

“The people here are really innocent and uneducated

This is the way (ojhas) sorcerers take advantage of the situation.” – Vijay Pathak, human rights activist

When women reject the sexual advances of their male neighbors, it is another cause on the list leading to allegations of witchcraft. Made to pay a heavy price because they have spurned a man, a woman can be declared a witch by an overly greedy ojha, who works closely with the accusing neighbor, causing the accused woman to be harassed, shunned from her village and worse.

Widows who refuse to relinquish claim over their husband’s property can similarly be threatened and charged with being a witch; an act that often succeeds to compel them to let go of their claim on their husband’s land.

Even though these are reoccurring, well-known and recognized situations in villages, most village members fail to acknowledge when a woman is falsely accused. To publically say they, “smell a rat,” is next to impossible.

While the ojha casts their “spell” over the village, creating a sense of fear and insecurity with tales of black magic, witchcraft, and horrific acts, the “real” reasons why women are branded witches for economic gain or sexual vengeance are completely forgotten.

Take another case of Bhuri Bai of Baman village in the Jhabua district. Almost three years ago, she was brutally beaten by her neighbors of many years, before being humiliatingly paraded through the village. Bhuri’s misery began when an ojha declared her responsible for the death of a child in the village.

Public Punishments as Violence Against Women

On the day of the boy’s funeral rites, a small piece of his flesh was said to have been found near his funeral pyre. The discovery caused swift gossip. The village ojha lost no time with the story. A case was built to cast suspicion upon Bhuri Bai as the “witch” who caused the death of the boy. These and other charges helped instigate the villagers to attack Bhuri.

As violence escalated, in efforts to protect Bhuri Bai, her husband Keshav barely managed to save her from the deadly blows of the villagers that followed.

Bhuri Bai is fortunate though, compared to many others who have been accused, there are countless others who have not escaped with their lives. According to the latest Jhabua district police records, over the last five years, 31 women were branded witches in the rural villages and beaten to death.

These are not the complete numbers. Every year, many more similar cases, involving various degrees of violence against women (VAW), occur in the Jhabua district. What is most troubling is that such events find only a quiet mention in government records, if at all.

“Witchcraft is common to the Jhabua, Dhar and Khargone districts, and women are usually treated as animals.” – Rahul Kumar, Indian veteran journalist

The attitude of the police towards these cases is, at best, disappointing and at worst, negligent. According to villagers, police simply encourage the parties involved to settle matters privately, without any formal legal action.

The critical point is that women, who are accused of witchcraft in India, will often not seek any legal or police assistance. Shame, isolation and poverty feeds the wheel of no protection, no rights and no dignity for women who are usually on the bottom layer of Indian society and already without any proper legal recourse.

The severity of deaths, due to witchcraft allegations, are caused by extreme and gruesome forms of torture, including acts of beheading, stoning, hanging, stabbing, poisoning or by being buried alive.

Can Rural Society in India Change?

“Victims are afraid to lodge a police complaint, fearing retaliation. After all, they have to live in the same village, amidst their tormentors,” explains Kumar.

In most cases, women are so humiliated that they cannot continue to live in their home village. In fact, the family of a mobbed woman also often ends up living like outcasts themselves. In violent episodes, and humiliating action, many relatives and extended families of women who have been accused of witchcraft are also forced to flee their homes and village regions.

According to the most recent data, approx 137 women accused of being a “witch” have been killed in violent acts connected to accusations against them in the region (2004 2009). These deaths are not easy and often include great suffering through public torture and humiliation.

According to the most recent data, approx 137 women accused of being a “witch” have been killed in violent acts connected to accusations against them in the region (2004 2009). These deaths are not easy and often include great suffering through public torture and humiliation.

It is suspected nationwide in India today that the actual number of deaths due to witchcraft allegations may be much higher than reports indicate.

Even with reported cases coming in lower than expected, “Less than 1% of reported cases actually lead to conviction,” says the Free Legal Aid Committee, a legal consultation advocacy group that works to help women in the eastern regions of Jharkand and Bihar in India.

45 year old Bihari Dalit woman, Lalpari Devi, is publically humiliated as she is tied to a tree and her hair is shaved.

Are Legal Protections Available?

While a woman accused of being a witch has a future that may not be certain, the Chhattisgarh government is trying to create laws that will stand for some type of legal protective action.

“Nobody will dare to attack her again,” declared one of the Chhatisgarh police officers involved in Mita Bai’s case.

Legislation in Chhatisgarh is now making the charges of witchcraft a non-bailable offense, but it comes with an unbalanced and unfair treatment of the women who are suffering the most. It includes a “protective” prison term for the alleged “witch” of up to five years.

This clearly flawed attempt at a solution, while trying to offer physical safety for women, could add more harm than good to women accused of witchcraft. The new law comes as legislators try to provide a buffer of safety for a women accused of being a witch as she is separated from her attackers. It also attempts to give accusers, “an alternate recourse against women besides the violence,” say local legislators.

But the law does not recognize the need to severely punish, first, those who are attacking the accused women. Instead it outlines a program of punishment aimed at the woman and refuses to provide dignity and respect for women who have faced unjust allegations.

Some laws in India do punish those who commit violence against women in cases of witchcraft allegations. Those who are integral in causing the problem, though, like the village ojha, who is the one who publicly “names a woman a witch,” are rarely sentenced to over six months.

Those who are accused of committing the violent act itself against a “witch” are usually sentenced to no more than one year. Those accused of murder often get reduced judgments or overturned sentences, as India’s current court system cannot adequately handle fair jurisprudence in cases involving superstition and witchcraft.

The ineffectiveness of courtroom justice concerning cases of women who have been severely injured, damaged or killed by allegations of witchcraft does more than involve issues of superstition. It involves international human rights law.

“The state of Jharkhand is deviating from International law obligations requiring India to address and prevent the problem of witch-hunting, which has resulted in the deaths of hundreds of women.” – Cornell Law School International Human Rights Clinic, petition to the High Court of Judicature, Ranchi, Jarkhand State, India January 2010

“The continued perpetuation of witchcraft related violence violates many international human rights that women are possessed of,” states the petition, “including their right to equality and non-discrimination, the right to life, the right to be free from cruel and inhuman treatment, the right to security, the right to adequate housing, the rights to access national tribunals, and the obligation to provide effective measures for relief.”

“International courts mandate that this Court (High Court of Judicature, Jarkhand State, India) must take action to provide effective judicial remedies for violations of these integral human rights,” the appeal continues.

Four states in India have approved protective anti-witchcraft laws, but they are still ineffective to protect most women accused of witchcraft. Police protections, courtroom decisions and legal representations need much more improvement. Education on the issues surrounding violence of women, superstitions and belief, along with greater understanding of equal human rights for women are essential to marking improvements.

Bihar, was first to pass the Prevention of Witch (Dayan) Practices Act of 1999. This was followed by Jharkhand’s Anti-Witchcraft Act in 2001 along with the 2005/2006 Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan laws.

Very recently, on March 12, 2010, the Indian Supreme Court in New Delhi refused to hear a petition called “The Witchcraft Act,” that asked for local regional cases involved with witchcraft allegations, to be allowed to enter the highest courtrooms within their regions. Witchcraft cases, if they can make it to court, are currently kept only in the lower court system without option for any higher court appeal.

Click website link and scroll down article to VIDEO. For further information about Women News Network please visit: http://womennewsnetwork.net

Human rights defender and activist, 70 year old, Birobala Rabha, has been fighting superstitions in Thakuvila, Assam, India for many years to help to liberate women in the region who have been charged with witchcraft. This 2:17 min video is part of a February 2010, IBN.Live news release.

To support this case, please click here: SEND APPEAL LETTER

SAMPLE LETTER