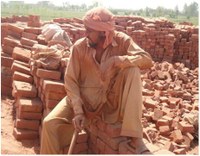

Over four million brick kiln workers in Pakistan are bonded labourers, tied by debt to their employers. Credit: Irfan Ahmed/IPS

One does not always need a time machine to travel into the past — a visit to a typical brick kiln in Pakistan’s Punjab province is enough to evoke a time when human beings were traded like animals and slavery was rampant.

Overburdened by loans, generation after generation of workers, totaling about 4.5 million spread across 18,000 kilns around the country, toil for nothing more than the promise of freedom.

Ata Muhammad (28) and his wife work for 18 hours a day at a kiln in the outskirts of Lahore, where they are paid 450 rupees (roughly 4.8 dollars) per 1,000 bricks, irrespective of how long it takes to complete the task.

According to estimates from the labour department, it takes a standard family of five, including children, a whole day to make 1000 bricks.

A study by the Centre for the Improvement of Working Conditions and Environment found that “a family of two adults and three children can make 500-1200 bricks a day depending on their skill (level) and physical health.”

The tasks include fetching mud from two or three kilometres away, soaking it in water, molding it into bricks, transporting the finished product to the kiln and finally baking and grading each brick.

In case of inclement weather or illness the workers earn nothing and are forced deeper into debt, begging for loans from their employers who are happy to extend the line of credit, which acts as a noose around the necks of many workers. Once indebted, workers cannot leave until they pay off their outstanding loans.

The loans, known as an ‘advance’, or ‘peshgi’ in Urdu, are the root of all kiln workers’ woes, according to Ghulam Fatima, secretary general of the Bonded Labour Liberation Front (BLLF), a rights group working to end bonded labour in Pakistan.

Children of kiln workers are born into bonded labour, working long hours alongside their parents. Credit: Irfan Ahmed/IPS

She says the kiln owners extend loans for occasions such as marriage, births and deaths, in an effort to tie the workers more tightly into servitude.

“This action is totally illegal, as ruled by the Supreme Court of Pakistan (in 1988). Under the law a kiln owner can only release an advance equal to or less than two weeks’ wages,” she told IPS.

For every 400-rupee payment that Ata is entitled to, the kiln owner deducts 150 rupees (about 1.6 dollars) to settle a loan he claims he granted Ata’s father, though Ata has no memory of this.

Fatima says this is totally unjust, as the minimum wage set by the government is 665.7 rupees (or seven dollars) per 1,000 bricks.

She added that numerous kilns pay a wage as low as 300 rupees (three dollars).

“If the government ensures payment of minimum wages to kiln workers and recovery of dues from owners, who have been paying less than the legal minimum, most of the workers will be able to clear their debts.”

As unregistered labourers, kiln workers are also denied social security cover. Since their employers do not set aside part of their wages for emergencies, they have no safety net upon which to fall in times of financial distress.

Related IPS Articles

If a contribution were made to a social security fund on their behalf, it would signal an end to the system of ‘advances’, according to Mehmood Butt, general secretary of the All Pakistan Bhatta Mazdoor (kiln workers) Union.

“If you get a marriage grant at the time of your daughter’s marriage, free medical care for you and your family at social security hospitals and even a death grant, why would you opt for exploitative loans?” he asked.

Butt told IPS that families of kiln workers carry price tags equivalent to their outstanding loans. By paying this amount, owners can effectively ‘purchase’ workers from one another.

If a worker runs away from a kiln, he is traced with the help of police and local politicians and all the money spent during this exercise is then added to his or her outstanding debt, according to Butt.

A lack of identification documents adds another restriction to kiln workers’ mobility. Khalid Mehmood, president of the Labour Education Foundation (LEF), pointed out that the Computerised National Identity Card (CNIC) — the right of every Pakistani — is the prerogative of but a few kiln workers.

“Once you have a CNIC, you can apply for social security registration, get enrolled on voting lists, benefit from welfare schemes, open bank accounts or apply for jobs. Kiln owners cannot afford all this,” he said.

Mehmood told IPS that the National Database Registration Authority (NADRA) set up mobile camps near some kilns close to Lahore earlier this year, with the intent of issuing CNICs to bonded labourers. But armed gangsters hired by kiln owners prevented all but a few from actually reaching the mobile centres.

Shaukat Nizai, media spokesperson for the Punjab labour department, believes bonded labour cannot be eradicated without empowering the workers through education.

This, he says, will enable them to live and find sustenance away from the remote kilns where they were born and where many expect to die.

Without alternative skills and knowledge, he told IPS, kiln workers and their families are doomed to a lifetime of toiling in the heat, never breaking the metaphorical chains of their bondage.

Shaukat told IPS that a project called the Elimination of Bonded Labour in Kilns (EBLIK), launched in 2009 in the district of Kasur in Lahore, has worked with the ministry of labour to establish 200 schools to educate 8,000 kiln workers’ children.

“It was not easy. It took us a long time to convince the kiln owners that this would help them as well.”

He added that the government has also started issuing soft loans to kiln workers to eliminate the advance payment system.

The government is also in talks with kiln owners regarding registration of workers with the social security department. Additionally, it has set up a helpline and a complaint cell, both of which assist workers in demanding minimum wage and other rights granted to them under the law.